Alor’s healing plants: a treasure trove of medical knowledge and oral tradition

- Written by Francesco Perono Cacciafoco, Associate Professor in Linguistics, Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University

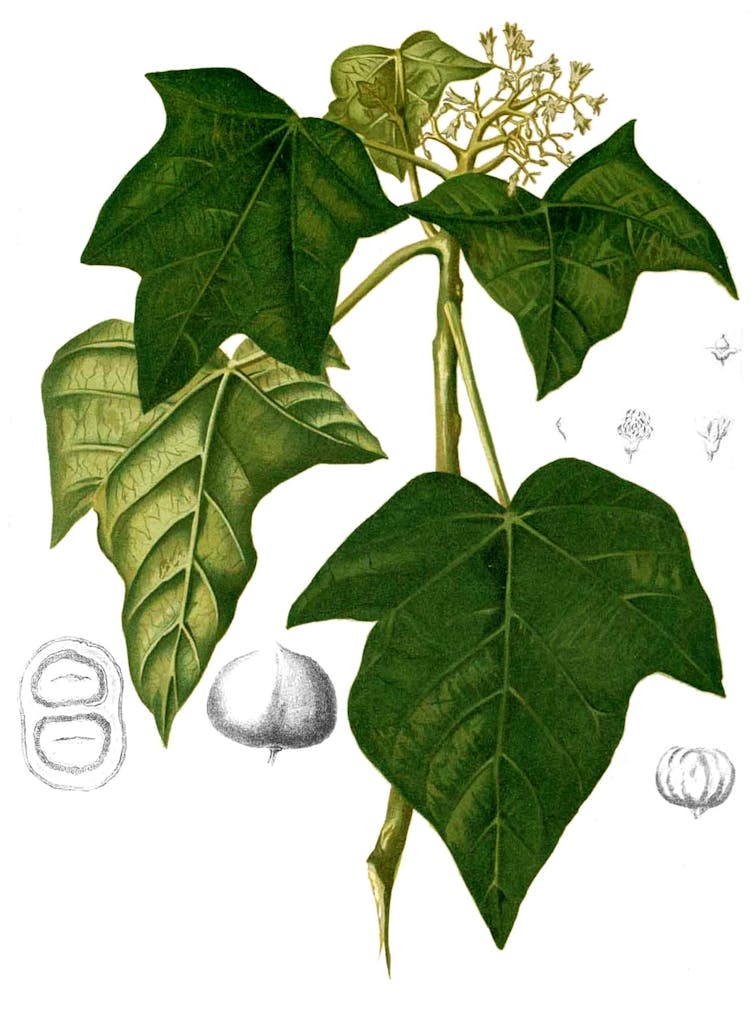

“When a child has a fever, crush a ‘candlenut’ (fiyaai [Aleurites moluccanus[1]]). Add water to the mixture, and apply it to the child’s body. The fever will go down.”

This healing formula doesn’t come from a section of the ‘Hippocratic Collection’[4] or the ‘Salernitan Guide to Health’[5], two of the most famous collections of ancient and medieval medical knowledge.

It is an Abui[6] oral prescription from Alor[7], a small island from Eastern Indonesia. My team and I[8] collected it and many others during our language documentation[9] fieldwork.

Read more: Finding 'Kape': How Language Documentation helps us preserve an endangered language[10]

Indigenous Indonesian communities — like the Papuan[11] Abui people of Alor — are the custodians of very ancient knowledge. Their traditional healing practices rely on the masterful use of medicinal plants.

Through years of fieldwork and research, we have documented how the names of local healing plants[12], their properties, and the related treatments are integrated into everyday conversation and practice among Indigenous communities. These names even shape local human geography (toponyms)[13] and the plots of legends and folktales[14].

In short, those plant names are more than just vocabulary items in endangered or undocumented languages. They provide us with leads to a treasure trove of medical knowledge, cultural history, and unrecorded oral traditions.

Collecting the names, understanding the culture

Our studies on local phytonyms[15] and medicinal plants represent an interdisciplinary effort originating from language documentation. We combine ethnobotany[16] with field linguistics[17] to document mainly Papuan Indigenous contexts from Southeast Indonesia (Alor-Pantar Archipelago) — including Abui, Kape[18], Papuna[19], Kamang[20], Kabola[21], Kula[22], and Sawila[23].

Collecting and analysing plant samples and their names involves working closely with Indigenous speakers — through direct and systematic interviews — as well as fieldwork and the development of an ongoing database. To ensure taxonomic accuracy, we verify every identification with botanists from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.[24][25]

For every plant, we record more than just its scientific classification and specimen data. We document its local name, English translation, and cultural roots[26] — uncovering the oral traditions, ancestral medical practices, and unwritten histories attached to each species.

This interdisciplinary work proves that medicinal properties, undocumented stories and myths, and ancestral beliefs are deeply[27] and intricately interwoven[28].

Intertwined practices and heritage

Beyond their medicinal use, plants and fungi are woven into the cultural beliefs and traditions of the Abui people. They shape a complex system of Indigenous knowledge.

Take the ruui haweei, or ‘rat’s ears’ mushroom (Auricularia polytricha[29]). Pregnant women eat this in the hope that their children will be born with beautiful ears.

Then there is the naai or ‘pigeon pea’ (Cajanus cajan[30]). This plant is used to treat diseases in children believed to be caused by their father’s adultery.

In this ritual, healers serve cooked pea porridge to the mother. The number of seeds left behind in the pot is said to reveal the number of women the husband has slept with. According to local belief, this revelation heals the sick child.

Plants also play a role in conflict resolution. During tribal wars, the luul meeting or ‘long pepper’ (Piper retrofractum[33]) was used to symbolically cleanse the ‘warm blood’ spilled in battle. By eating the roots or nuts, villagers purified the bloodshed, allowing them to share meals again and chew betel nuts[34] in peace.

Finally, the bayooqa tree (Pterospermum diversifolium[35]) bridges the gap between medicine and the spirit world. While its leaves treat wounds and dysentery, its wood is sacred. It was traditionally used to build worship platforms for the ancient god ‘Lamòling[36]’.

Locals used these platforms in a ritual called bayooqa liik hasuonra (‘pushing down the platform’), performed forty days after a burial. Family members shared a ritual meal on a wooden slab before cutting down the posts and flipping the platform over — a final farewell to their relative.

Linguistic map of the Alor-Pantar Archipelago (Southeast Indonesia)

Author provided, Author provided (no reuse)

Linguistic map of the Alor-Pantar Archipelago (Southeast Indonesia)

Author provided, Author provided (no reuse)

Our findings show that healing plants are not only central to the daily medicinal needs of Indigenous Papuan communities, but are also part of a deep-rooted cultural heritage. This knowledge shapes their local identity and guides them through every stage of life — from birth to death.

References

- ^ Aleurites moluccanus (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ PROTA4U (prota.prota4u.org)

- ^ CC BY-NC-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ ‘Hippocratic Collection’ (www.britannica.com)

- ^ the ‘Salernitan Guide to Health’ (www.britannica.com)

- ^ Abui (glottolog.org)

- ^ Alor (www.britannica.com)

- ^ My team and I (scholar.xjtlu.edu.cn)

- ^ language documentation (www.oxfordbibliographies.com)

- ^ Finding 'Kape': How Language Documentation helps us preserve an endangered language (theconversation.com)

- ^ Papuan (www.britannica.com)

- ^ names of local healing plants (www.mdpi.com)

- ^ (toponyms) (cbg.uvt.ro)

- ^ legends and folktales (anale-lingvistica.reviste.ucv.ro)

- ^ phytonyms (en.wiktionary.org)

- ^ ethnobotany (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ field linguistics (www.oxfordbibliographies.com)

- ^ Kape (theconversation.com)

- ^ Papuna (glottolog.org)

- ^ Kamang (glottolog.org)

- ^ Kabola (glottolog.org)

- ^ Kula (glottolog.org)

- ^ Sawila (glottolog.org)

- ^ taxonomic (www.britannica.com)

- ^ Kew. (www.kew.org)

- ^ cultural roots (blogs.ntu.edu.sg)

- ^ deeply (anale-lingvistica.reviste.ucv.ro)

- ^ intricately interwoven (link.springer.com)

- ^ Auricularia polytricha (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ Cajanus cajan (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ PROTA4U (prota.prota4u.org)

- ^ CC BY-NC-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Piper retrofractum (www.gbif.org)

- ^ betel nuts (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ Pterospermum diversifolium (www.gbif.org)

- ^ Lamòling (www.sciencedirect.com)

Authors: Francesco Perono Cacciafoco, Associate Professor in Linguistics, Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University