China’s WWII anniversary parade rekindles cross-strait battle over war narrative − and fears in Taiwan of future conflict

- Written by Meredith Oyen, Associate Professor of History and Asian Studies, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

World War II casts a very long shadow in East Asia. Eighty years after ending with Japan’s surrender[1] to Allied forces on Sept. 2, 1945, the conflict continues to stir debate over the past, in the context of today’s geopolitical tensions.

China’s high-profile military parade[2] commemorating the conclusion of what Beijing calls the “War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression[3]” is a case in point.

In the run-up to the Sept. 3, 2025, event, the Chinese Communist Party has been criticized in Tokyo for stoking anti-Japanese sentiment[4] and in the U.S. for downplaying America’s role while playing up Russia’s[5].

But as an expert on Taiwan-China relations[6], I’m interested in the battle over the narrative[7] between Taipei and Beijing. During World War II, China’s communists and nationalists became uneasy internal allies, putting their civil war on pause to unite against Japan. Afterward, the communists prevailed and the nationalists fled to Taiwan, where they set up their own government – one the mainland has never recognized. Months of bickering over the commemorations shine a light on how both sides view their respective roles in defeating Japan – and what the show of military force by Beijing signals today.

To whom did Japan surrender?

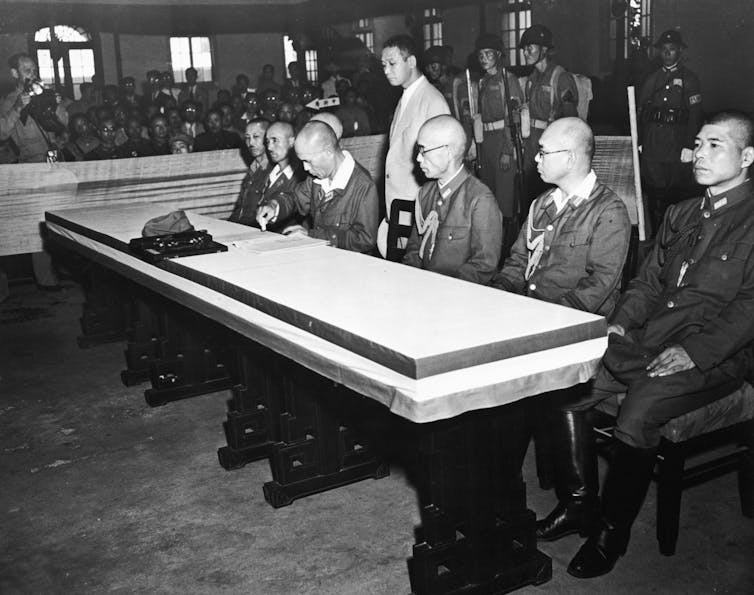

A peculiarity of the current commemorations is that Japan did not actually surrender to Communist China, or technically to China at all. On Sept. 9, 1945, a week after agreeing to the terms laid out[8] by the Allied forces, Japan, at a ceremony in Nanjing, formally surrendered to China’s National Revolutionary Army – the military wing of the nationalist Kuomintang led by Chiang Kai-shek.

And this gets to the heart of why many in Taiwan – where the nationalists fled at the conclusion of China’s civil war in 1949[10] – are unhappy with Beijing’s projection of Communist China as the victors against Japan.

By the time that war in East Asia took hold, in 1937, China was a decade[11] into its own civil war between the nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong’s communists.

The nationalists and communists fell into an uneasy truce with the creation of the second united front[12] in 1937. But the role of both sides in fighting the Japanese has long been the source of disagreement.

The nationalist army bore the brunt of conventional warfare. But it was criticized for being disorganized and too dependent on men forced into service. Those soldiers were often ill-trained and underfed.

To the communists, the army – and its failings – were the product of the corrupt government under Chiang. And it was largely responsible for China’s inept response to Japan’s initial advances.

In Beijing’s telling today[14], it was the communist forces, which relied more on guerrilla tactics, that helped push back the Japanese.

Conversely, the nationalists cast events during World War II very differently. China’s nationalist administration under Chiang was the first government in the world to fight a fascist power.

For eight or even 14 years, depending on whether you date the start of the conflict to 1937 or 1931[15], the nationalist army fought hard and sacrificed a lot as it put up the bulk of the resistance against Japan. To Taiwan’s Chinese nationalists, the Chinese communist contribution was minimal.

Worse, to them, the communists took the opportunity of Japan’s invasion to further their own position[16] against the nationalists. Indeed, when the civil war began again after Japan’s defeat, Mao’s communists had the upper hand, leading to the nationalists’ retreat to Taiwan four years later.

From Japanese to Chinese rule

The status of Taiwan at the end of World War II presents another wrinkle. By then, the island had been under Japanese colonial control since 1895[17]. Indeed, a second surrender ceremony took place on Oct. 25, 1945, when the Japanese forces in Taiwan surrendered to a nationalist official[18] who had come over from the mainland.

What followed was a period of Chinese nationalist takeover of Taiwan and a corresponding Japanese retreat – it took several years for all Japanese officials and families to be repatriated to Japan.

Meanwhile, the nationalist Kuomintang that came into Taiwan were not terribly well received by the local population, many of whom were hoping for independence and resisted[19] a Chinese nationalist, authoritarian takeover.

Complicating matters was that a 1943 agreement between the leaders of the Allied nations in Cairo declared[20] that in the event of Japan’s defeat, Formosa, as Taiwan was then called, would be returned to the Republic of China.

But now you had two claimants to being “China” – the communists on the mainland and the nationalists on Taiwan. Either way, the Cairo Declaration served the interests of the “One-China” principle – under which both Beijing and Taipei view Taiwan as part of unified China, but differ over which is the country’s legitimate government – over that of those seeking the island’s formal independence from the mainland.

From the past to the future

The conflicting war narratives[22] from Communist China, pro-unification nationalists in Taiwan and those seeking the island’s independence have been present since the end of World War II – and they tend to flare up around commemorations and anniversaries.

They did so[23], for example, when China held a big military celebration in 2015 to commemorate the 70th anniversary of Japan’s surrender.

This year’s event seeks to do a couple of things. First, Beijing is using it to reshape the memory of the Chinese Communist Party’s role in the world as a result of World War II.

The war is seen as a critical moment in Chinese history – not just in the context of defeating Japan and its role in the subsequent founding of the People’s Republic, but because in Asia it marked the end of the colonial era. During the war, foreign powers in China gave up their concessions and ended a century of partial colonial control over port cities such as Shanghai.

The war also marked China’s emergence as a major player on the world scene. As a result of its contributions in World War II, China gained a role on the United Nations Security Council[24]. The Republic of China on Taiwan maintained that seat and that vote until 1971, when U.N. recognition finally shifted to the People’s Republic of China.

In recent years, promoting a prominent role in defeating fascism and shaping the postwar world order has been particularly important as China looks to carve out a space for itself in a multipolar world and show an alternative to a world dominated by the United States and Western Europe.

For these reasons, Beijing is keen to keep focus[25] on its preferred narrative, highlighting communist contributions to the war effort.

But given Beijing’s adherence to the one-party principle, Taiwan – as part of China – could not be ignored. So, invites to Taiwanese officials to the commemorative events were sent out.

Representatives from the pro-independence ruling Democratic People’s Party and the main opposition party, the pro-unification Kuomintang, have largely declined to attend. The executive government has said[27] that no current government officials in Taiwan should attend the military parade. Nonetheless, on Sept. 2, former Kuomintang chairperson Hung Hsiu-chu announced that she would be in Beijing[28] for the event.

For its part, Taiwan has opted for more low-key commemorations of the end of Japanese rule of the island.

Many Taiwanese are much more concerned about current events than those of 80 years ago. The anniversary comes at a time of increased tension across the Taiwan Strait. Echoing concern over Chinese military might and potential intent, earlier this year “Zero Day Attack” – a new series[29] depicting a future, fictionalized invasion of the island by the People’s Republic of China – dropped and has since become hugely popular.

Its streaming launch date[30] in Japan was Aug. 15 – the 80th anniversary of the announcement of Japan’s surrender in World War II.

This article is based on a conversation between Meredith Oyen and Gemma Ware for The Conversation Weekly podcast that will be available later this week. Subscribe to The Conversation Weekly podcast[31].

References

- ^ Japan’s surrender (www.archives.gov)

- ^ high-profile military parade (apnews.com)

- ^ War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (english.scio.gov.cn)

- ^ criticized in Tokyo for stoking anti-Japanese sentiment (english.kyodonews.net)

- ^ downplaying America’s role while playing up Russia’s (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ expert on Taiwan-China relations (history.umbc.edu)

- ^ battle over the narrative (www.npr.org)

- ^ the terms laid out (history.state.gov)

- ^ Bettmann/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ conclusion of China’s civil war in 1949 (history.state.gov)

- ^ a decade (history.state.gov)

- ^ second united front (www.geopoliticalmonitor.com)

- ^ History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ telling today (www.reuters.com)

- ^ date the start of the conflict to 1937 or 1931 (www.pacificatrocities.org)

- ^ further their own position (www.pacificatrocities.org)

- ^ Japanese colonial control since 1895 (internationalcomparative.duke.edu)

- ^ Japanese forces in Taiwan surrendered to a nationalist official (www.taiwandocuments.org)

- ^ hoping for independence and resisted (taiwantoday.tw)

- ^ between the leaders of the Allied nations in Cairo declared (digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org)

- ^ Keystone/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ conflicting war narratives (www.yahoo.com)

- ^ They did so (archive.nytimes.com)

- ^ China gained a role on the United Nations Security Council (www.ebsco.com)

- ^ keen to keep focus (paper.people.com.cn)

- ^ VCG/VCG via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ has said (focustaiwan.tw)

- ^ announced that she would be in Beijing (focustaiwan.tw)

- ^ a new series (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ launch date (news.cgtn.com)

- ^ Subscribe to The Conversation Weekly podcast (pod.link)

Authors: Meredith Oyen, Associate Professor of History and Asian Studies, University of Maryland, Baltimore County