Opera is not dying – but it needs a second act for the streaming era

- Written by Christos Makridis, Associate Research Professor of Information Systems, Arizona State University; Institute for Humane Studies

Every few years[1], you’ll hear a familiar refrain: “Opera is dying.”

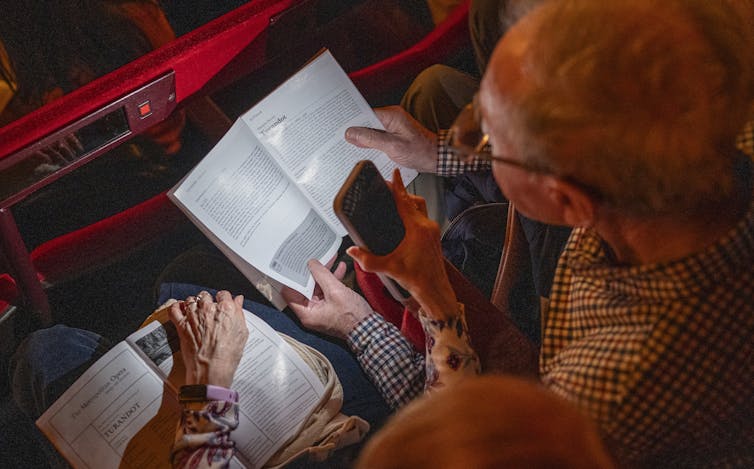

National surveys point to[2] slumping attendance[3] at live performances. Audiences are aging, leaving fewer fans to fill seats at productions of “La Bohème,” “Carmen,” “The Magic Flute” and the like, while production costs grow.

I’m a labor economist[4] who studies the economics of art and culture. To assess the state of opera in the U.S., I analyzed financial data collected by Opera America, an association whose roughly 600 members are overwhelmingly nonprofit opera companies.

After crunching the numbers[5], as I explained in a 2026 paper published in the Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, I reached a surprising conclusion about the state of those nonprofits.

Funding model is faltering

Although opera companies are experiencing financial stress[6], opera isn’t a dying art form. Instead, I found that the public’s demand for meaningful, live cultural experiences – including opera – remains strong.

That said, opera’s traditional business model is faltering.

Opera is, for the most part, stuck in the past[7]. Many companies still depend on a business model that relies on season ticket sales and a small circle of big donors. This approach worked better in the 20th century than it does now.

Few opera companies have embraced strategies the rest of the entertainment industry regularly uses: audience data analysis, experimentation with digital content and streaming, and engagement through online platforms rather than brochures.

In other words, opera management practices, metrics and audience development tactics didn’t change much[8] even as the world transitioned into the digital age.

Change is needed because subscriptions and individual ticket sales have declined for many companies, especially those with budgets above US$1 million.

The number of opera tickets those companies sold fell 21% between 2019 and 2023[9]. Ticket revenue fell 22% over the same period.

Meanwhile, opera companies received 19% of their budgets[10] from donations and grants in 2023, down from roughly 25% in 2019, as earned revenue weakened and fundraising failed to fully recover.

Opera companies receive more than twice as much funding from philanthropy as from government sources. Government support was low and relatively stable prior to 2020 and rose sharply during the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic[11] before declining again to roughly 8% of operating revenue by 2023.

Managing institutions in trouble

I don’t dispute that opera’s economic woes are troubling. But I don’t see them as a sign that this art form is in cultural decline. Instead, I believe that opera institutions need to modernize how they operate.

Audiences continue to respond to the repertoire when companies find new ways to tell familiar stories.

Productions of canonical works such as La Traviata and Don Giovanni that place well-known narratives in contemporary settings or reframe them through modern staging have drawn strong attendance and critical attention. Crossover projects that bring operatic voices into dialogue with jazz, musical theater or popular musical performance have also sold out limited runs aimed at new audiences.

And smaller-scale formats, including chamber operas and performances staged in studios or alternative venues, have consistently filled seats – even as large main-stage productions struggle to sell tickets.

Those examples point to underlying demand for experiencing operas[13] – even if fewer people are buying season tickets.

To be sure, there are some signs of progress. Some opera companies are taking their digital productions seriously.

Boston Baroque is primarily an orchestra and chorus, but it also produces staged operas[14]. It offered livestreams of its performances during the pandemic to earn extra money.

New York City’s Metropolitan Opera has maintained a standalone direct-to-consumer subscription product, Met Opera on Demand[15], that anyone in the world can access. But it illustrates the strategic tension many companies face: Digital expansion can broaden reach, but it may also complicate efforts to fill empty seats.

This 1968 recording of Luciano Pavarotti conveys the power of the opera at its best.Grappling with an economic problem

Opera’s biggest challenge is structural, not artistic[16].

Live performance is inherently labor intensive[17] – and expensive. You cannot automate a string quartet or speed up an aria without destroying what makes it valuable.

Notably, opera companies have nearly doubled administrative costs as a share of their budgets since the mid-2000s, while spending on artistic programming has remained flat.

Some of the increase in administrative spending reflects the growing complexity of fundraising, compliance and labor management. But the magnitude of the shift strongly suggests declining organizational efficiency, with managerial and overhead functions expanding faster than opera’s capacity to stage productions or build its audience in the United States.

Meanwhile, ticket sales have declined and the number of major opera donors has declined.

Facing a similar turning point

Financial distress is not unique to opera.

Many U.S. orchestras have confronted serious financial stress, including bankruptcies and closures in places like Honolulu[18], Syracuse, N.Y.[19] and Albuquerque, N.M.[20].

The orchestras that survived tended to diversify revenue, analyze data and treat innovation as part of their mission – three strategies opera companies have failed to pursue consistently.

Reaching the public where it already is

The assumption that younger generations do not care about classical music is unfounded.

When opera companies put performances on streaming platforms during the pandemic, many younger listeners tuned in.

A 2022 survey[21] of music consumption in the United Kingdom conducted by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; Deezer, one of several global services tracking the digital consumption of classical music; and the British Phonographic Industry found that 59% of people under 35 streamed orchestral music during the COVID-19 lockdown, compared with a 51% national average across all age groups.

Meanwhile, classical music streaming rose sharply across digital platforms during the first months of the pandemic. Deezer reported a 17% increase in classical streams in the 12 months beginning in April 2019.

These patterns suggest that younger audiences can become interested in opera and classical music when access to those genres is easy, and that digital formats can meaningfully expand the base of younger listeners.

But younger audiences usually encounter the music they listen to through algorithms or short-form video.

Treating performances as content

The lesson is not that opera should abandon live performance – if anything, everyone needs more, not less, in-person interaction in this hybrid-work era. Instead, I believe that opera companies should treat performances as content that can be accessed both in person and in digital spaces.

That way, they can spread those fixed artistic costs across multiple formats and markets, whether they’re recordings, livestreams, educational licenses or smaller-scale spinoff events.

Opera has survived wars[22], depressions, technological revolutions and cultural upheavals because it evolved. Today, the risk is not that people have stopped caring about music; it’s that opera companies have presumed that upholding tradition requires a rigidity at odds with their own success.

References

- ^ Every few years (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ National surveys point to (www.operaamerica.org)

- ^ slumping attendance (observer.com)

- ^ labor economist (scholar.google.com)

- ^ crunching the numbers (doi.org)

- ^ experiencing financial stress (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ stuck in the past (www.insidephilanthropy.com)

- ^ didn’t change much (static1.squarespace.com)

- ^ fell 21% between 2019 and 2023 (www.operaamerica.org)

- ^ opera companies received 19% of their budgets (www.operaamerica.org)

- ^ first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic (www.arts.gov)

- ^ Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ underlying demand for experiencing operas (www.aesthetics.mpg.de)

- ^ produces staged operas (www.wgbh.org)

- ^ Met Opera on Demand (www.metopera.org)

- ^ structural, not artistic (static1.squarespace.com)

- ^ inherently labor intensive (www.ebsco.com)

- ^ Honolulu (www.hawaiinewsnow.com)

- ^ Syracuse, N.Y. (theviolinchannel.com)

- ^ Albuquerque, N.M. (symphony.org)

- ^ 2022 survey (www.ludwig-van.com)

- ^ Opera has survived wars (www.sfopera.com)

Authors: Christos Makridis, Associate Research Professor of Information Systems, Arizona State University; Institute for Humane Studies