Marine protected areas aren’t in the right places to safeguard dolphins and whales in the South Atlantic

- Written by Guilherme Maricato, Pós-doutorando no Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia, UFRJ

The ocean is under increasing pressure. Everyday human activities, from shipping to oil and gas exploration to urban pollution, are affecting the marine environment. Extensive research shows how this combination of stressors represents one of the greatest threats to marine wildlife, potentially affecting biodiversity on a global scale[1].

To protect the ocean, one of the primary tools we have is marine protected areas[2]. But are they truly protecting species in the most critical locations?

In an attempt to answer this question in Brazil, we conducted a comprehensive study focusing on two key species: the Bryde’s whale[3], a nonmigratory species, and the bottlenose dolphin[4], found in coastal and oceanic waters around the world. We chose these species because they do not migrate and stay in the same areas all year long, where they are exposed to harmful human activities.

The news is unfortunately not good: Our findings, recently published in Marine Pollution Bulletin[5], show that the areas critical for these species’ survival are also the most threatened.

Where whales and dolphins eat and play

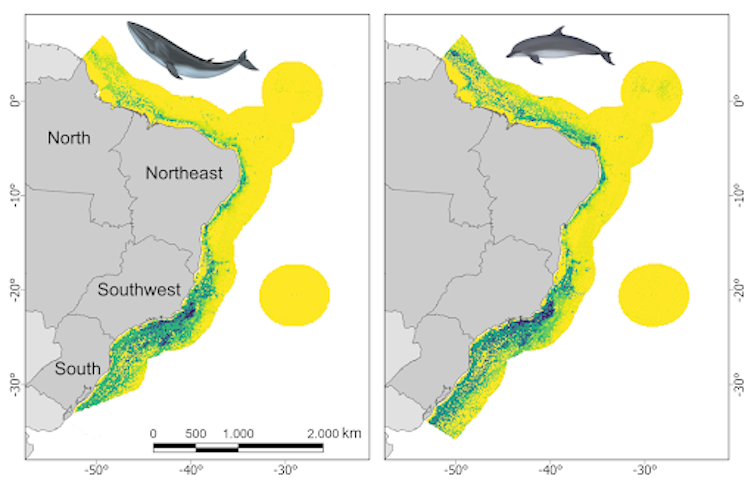

Through spatial analysis, specifically species distribution models[6], we uncovered these animals’ preferences. We cross-referenced thousands of occurrence records for Bryde’s whales and bottlenose dolphins with environmental data that can influence their presence. This included factors such as water temperature, depth and even food availability.

From this data, we created a map showing the most suitable habitats for these species. The results strongly indicated that southeastern Brazil is their “preferred area.” On the continental shelf[7], these areas are located in shallower waters rich in nutrients, often associated with colder waters and steep seabed slopes that bring food to the surface.

The problem with overlap

The preferred areas we identified, however, are not exclusive to whales and dolphins. Southeastern Brazil is also an economically vital marine region for the country, driven by activities in the Santos and Campos basins[8], where a new oil reserve was recently discovered.

In the second stage of our research, we overlaid our map of the most suitable habitats for these species with a map of human activity. This included the presence of ports, areas of oil and gas exploration, and various shipping routes.

The result is a near-perfect overlap. The areas where Bryde’s whales and bottlenose dolphins are most frequently found coincide exactly with where human activity is most intense.

Why protected areas aren’t helping them

Brazil has expanded its conservation coverage in recent years by creating four large marine protected areas[9], which we think is excellent news. However, the crux of the matter lies in the quality of that protection.

In 2024, we also participated in a global collaborative effort to evaluate marine protected area effectiveness, the results of which were published in Marine Policy[10]. The findings revealed that the vast majority of Brazil’s designated protected areas actually permit activities that are incompatible with biodiversity conservation.

This quality gap was also evident in our study. Most marine protected areas in southeastern Brazil, even the most effective ones, are coastal. They do not encompass the suitable habitats for Bryde’s whales and bottlenose dolphins, which are more heavily affected by oil and gas exploration.

And what about the oceanic protected areas Brazil created?

For the most part, they are located in areas that are either not the most suitable for these two species or lack significant conflicts with human activity. There is an ongoing debate[11] about whether governments are protecting the right places or leaving the most critical biodiversity hot spots and conflict zones unprotected.

The real impacts of the conflict

The risk of ship strikes is constant. Whales and dolphins must come to the surface to breathe, and in areas of heavy traffic such as southeastern Brazil, the risk of being hit by vessels is high. Meanwhile, constant noise – from both ship engines and oil and gas exploration – interferes with the navigation, communication and foraging of these animals.

Additionally, there is the risk of entanglement in fishing nets, particularly in areas with intense fishing activity, resulting in bycatch[12], the incidental capture of nontarget species. Finally, pollution from ports along with potential spills can degrade the health of these animals and weaken their immune systems.

How the preferred habitats of Bryde’s whales, left, and bottlenose dolphins, right, overlap with human activity. Dark colors indicate a higher exposure index.

Guilherme Maricato

How the preferred habitats of Bryde’s whales, left, and bottlenose dolphins, right, overlap with human activity. Dark colors indicate a higher exposure index.

Guilherme Maricato

A road map for the future

Our findings serve as a critical warning: Simply creating marine protected areas is not enough. They must be placed in the right locations, protecting species where they are most vulnerable. We have shown that there is an urgent need to rethink conservation strategies in Brazil.

In addition to strengthening the network of marine protected areas, our findings suggest the need for specific management actions to reduce conflicts. While reducing ship speeds can protect whales from collisions[13], establishing fishing exclusion zones[14] and using acoustic deterrents[15] can prevent dolphins from becoming entangled in nets.

Most importantly, however, we believe these actions must be applied in the areas of highest exposure for conservation to be truly effective. Protecting biodiversity while maintaining economic activity is a complex challenge, but we now have a map to begin this conversation.

This project was funded by the Foundation for Research Support of the State of Rio de Janeiro[16] (Faperj), Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education[17] (Capes) and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development[18] (CNPq). We also acknowledge the support of the Marine Ecology and Conservation Lab[19] (ECoMAR-UFRJ), Brazilian Humpback Whale Project[20], Ilhas do Rio Project[21], Cetacean Monitoring Project[22], Marine Mammal Monitoring Support System[23], Marine Conservation Institute[24] and Coral Vivo Project[25]. The publication of this article was also supported by Capes[26].

References

- ^ potentially affecting biodiversity on a global scale (doi.org)

- ^ marine protected areas (marine-conservation.org)

- ^ Bryde’s whale (www.fisheries.noaa.gov)

- ^ bottlenose dolphin (iwc.int)

- ^ recently published in Marine Pollution Bulletin (doi.org)

- ^ species distribution models (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ continental shelf (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ activities in the Santos and Campos basins (agencia.petrobras.com.br)

- ^ creating four large marine protected areas (news.mongabay.com)

- ^ the results of which were published in Marine Policy (doi.org)

- ^ There is an ongoing debate (doi.org)

- ^ resulting in bycatch (doi.org)

- ^ reducing ship speeds can protect whales from collisions (doi.org)

- ^ fishing exclusion zones (doi.org)

- ^ acoustic deterrents (doi.org)

- ^ Foundation for Research Support of the State of Rio de Janeiro (www.faperj.br)

- ^ Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (www.gov.br)

- ^ National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (www.gov.br)

- ^ Marine Ecology and Conservation Lab (ecomarufrj.com.br)

- ^ Brazilian Humpback Whale Project (www.baleiajubarte.org.br)

- ^ Ilhas do Rio Project (ilhasdorio.org.br)

- ^ Cetacean Monitoring Project (comunicabaciadesantos.petrobras.com.br)

- ^ Marine Mammal Monitoring Support System (simmam.acad.univali.br)

- ^ Marine Conservation Institute (marine-conservation.org)

- ^ Coral Vivo Project (coralvivo.org.br)

- ^ Capes (www.gov.br)

Authors: Guilherme Maricato, Pós-doutorando no Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia, UFRJ