Nearly every state in the US has dyslexia laws – but our research shows limited change for struggling readers

- Written by Eric Hengyu Hu, Research Scientist of Educational Policy, University at Albany, State University of New York

Families with children who have dyslexia have long pushed lawmakers to respond to a pressing concern[1]: Too many young students struggle for years to learn to read, before schools recognize the problem.

In response, nearly every state in the U.S. passed some sort of dyslexia laws[2] over the past decade. Most of these laws encourage or require schools to screen young children for reading difficulties, train teachers in evidence-based reading instruction and provide targeted support to students who show early signs of dyslexia.

Families of children with dyslexia[3], educators and[4] dyslexia advocacy groups[5] widely praised these laws. If schools could identify dyslexia early and respond with evidence-based instruction, reading outcomes would likely improve and fewer children would fall behind.

But what actually happened after these laws passed?

My colleagues[6] and I[7] examined nearly[8] two decades of national student data[9] to answer this question. The results tell a complicated story.

An undetected problem

Dyslexia is a brain-based[11] learning difference that makes reading words slow and effortful, even when children have typical intelligence and education.

About 5% to 15% of U.S. children experience persistent reading difficulties [12] consistent with dyslexia. Without early support, these difficulties can have long-term academic and emotional consequences[13].

Before the 2000s, dyslexia was rarely mentioned explicitly in education policy. Students with dyslexia were typically grouped under a broad learning disability category, often without focused instruction[14] or support.

Parent advocacy groups[15] and dyslexia advocacy organizations[16] began pushing lawmakers[17] in the early 2010s to recognize dyslexia in state education policy. They also lobbied for states to require early screening for reading difficulties and to teach reading with rigorous methods backed by scientific research.

Their advocacy coincided with a growing scientific consensus[18]: Early, explicit instruction in phonics and language structure helps struggling readers, including students with dyslexia.

Research and[19] advocacy also highlighted[20] that many children with reading difficulties were not identified until later in elementary school, after years of academic struggle, when gaps in reading skills are harder to correct.

States respond with dyslexia laws

A few states, like Texas[21] and Arkansas[22], first passed dyslexia laws in the early 2010s[23]. One central goal was to help schools identify dyslexia in students earlier, rather than waiting until these students experience repeated academic failure.

By the late 2010s[24], most states had adopted some form of dyslexia legislation.

As of 2025[25], all states except Hawaii have enacted dyslexia legislation.

While the laws shared similar goals of promoting early screening for reading difficulties, improving reading instruction and expanding support for struggling readers, they varied widely in strength, funding and expectations for schools.

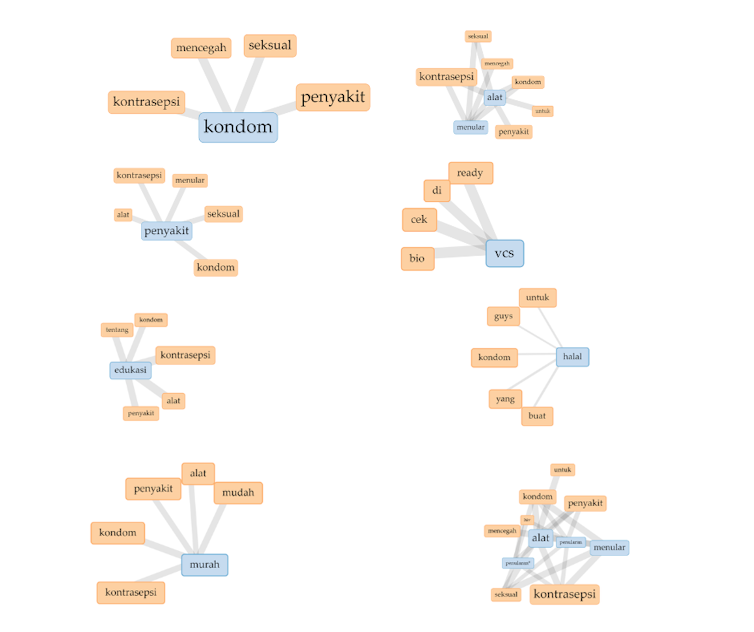

My colleagues and I wanted to examine whether the wave of state dyslexia laws that began in the early 2010s was associated with changes in students’ reading outcomes.

Mixed results

We analyzed[26] fourth grade reading assessments from the National Assessment of Educational Progress[27], often called the nation’s report card, from 2003 to 2022.

We focused on how often students were identified with reading-related learning disabilities and how well those students performed in reading. We compared trends before and after dyslexia laws were enacted across 47 states.

Two findings stood out:

• First, more than half of the states with these new laws showed no significant shift in identifying learning disabilities related to reading. Some states identified more students, some fewer, but there was no consistent national pattern.

• Second, reading achievement among students identified with learning disabilities often declined, rather than improved, after these laws passed in many states, including Alaska, Maine, Massachusetts, New York, Ohio and West Virginia.

Only four states – Arizona, Mississippi, Nevada and Oklahoma – showed significant gains in reading scores on state assessments, with average increases ranging[28] from 3 points in Oklahoma’s case to 10 points in Arizona’s example. Many other states experienced flat trends or declines over the same period.

Passing a law doesn’t equal classroom change

Our findings suggest that dyslexia laws often raised awareness about dyslexia and early reading difficulties without fully changing classroom practices.

Many states[29], such as Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts and North Carolina, required early screening for dyslexia – but did not ensure schools had trained staff, for example, on how to conduct this screening.

Even with enough teachers to screen for dyslexia, screening alone does not help students unless it is followed by high-quality instruction and sustained support[30].

Funding has been another major challenge. Most dyslexia laws were passed without dedicated funding for teacher training or instructional materials, leaving districts to absorb the costs. As a result, implementation has been uneven, with well-funded districts moving faster than others.

Teacher preparation also matters. Teaching reading effectively, especially for students with dyslexia, requires specialized knowledge that many teachers were never taught in their training programs. Without strong professional development and ongoing coaching, new mandates can be difficult to carry out.

Taken together, these factors help explain why dyslexia laws alone have not produced widespread gains.

What distinguishes states that improved

Despite the mixed national picture, students in some states, including Arizona and Mississippi, did better on reading outcomes after their schools adopted dyslexia-related policies. These states shared several features.

First, when young children in these states were flagged as at risk for reading difficulties, schools were expected to provide additional reading instruction – rather than treating screening as an end in itself.

Second, schools in these states invested in practical teacher training, focused on how to teach foundational reading skills – such as phonics and word decoding – that are especially important for students with dyslexia.

Third, these states aligned their dyslexia laws with broader literacy reforms – like using evidence-based reading curricula and providing coaching to teachers – rather than treating dyslexia policy as a stand-alone mandate.

Mississippi is often[31] cited as an example of a state that successfully paired dyslexia policy with a broader overhaul of reading instruction, resulting in a boost in reading achievement scores from 2013 to 2019. This overhaul included more structured reading instruction, teacher training and literacy coaches in schools.

Other states, including Louisiana[32] and Alabama[33], adopted similar approaches and also saw reading gains for kids with learning disabilities – including dyslexia – after they enacted their dyslexia laws.

The takeaway

Dyslexia laws recognize that struggling young readers deserve early, evidence-based support rather than years of delay. That alone is meaningful progress.

But two decades of national data suggests that legislation by itself is not enough.

If states want dyslexia laws to fulfill their promise, the next step is clear: Move beyond mandates and focus on how schools are supported to carry them out. For children struggling to learn to read, the difference between policy and practice can shape their entire educational future.

References

- ^ to respond to a pressing concern (dyslexiaida.org)

- ^ dyslexia laws (www.dyslegia.com)

- ^ Families of children with dyslexia (www.edweek.org)

- ^ educators and (e4e.org)

- ^ dyslexia advocacy groups (www.pr.com)

- ^ My colleagues (scholar.google.com)

- ^ and I (scholar.google.com)

- ^ examined nearly (scholar.google.com)

- ^ national student data (nces.ed.gov)

- ^ aldomurillo/Stock Photos/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ Dyslexia is a brain-based (dyslexiaida.org)

- ^ experience persistent reading difficulties (link.springer.com)

- ^ academic and emotional consequences (doi.org)

- ^ without focused instruction (doi.org)

- ^ Parent advocacy groups (www.decodingdyslexia.net)

- ^ dyslexia advocacy organizations (www.decodingdyslexia.net)

- ^ began pushing lawmakers (ncld.org)

- ^ scientific consensus (dyslexiaida.org)

- ^ Research and (doi.org)

- ^ advocacy also highlighted (www.decodingdyslexia.net)

- ^ like Texas (tea.texas.gov)

- ^ and Arkansas (dese.ade.arkansas.gov)

- ^ early 2010s (link.springer.com)

- ^ By the late 2010s (dyslexiaida.org)

- ^ As of 2025 (doi.org)

- ^ We analyzed (doi.org)

- ^ National Assessment of Educational Progress (nces.ed.gov)

- ^ with average increases ranging (doi.org)

- ^ Many states (doi.org)

- ^ high-quality instruction and sustained support (pubs.asha.org)

- ^ Mississippi is often (doi.org)

- ^ including Louisiana (doe.louisiana.gov)

- ^ and Alabama (www.alabamaachieves.org)

Authors: Eric Hengyu Hu, Research Scientist of Educational Policy, University at Albany, State University of New York