Health or economy? Making the best impossible decision in the face of COVID-19

- Written by Sri Astuti Thamrin, Ph.D/ Dosen Universitas Hasanuddin, Universitas Hasanuddin

When Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s largest economy, first began grappling with COVID in 2020, its government was widely criticised for choosing to save the economy[1] over people’s lives in its COVID-19 policies.

Initially, the government shut down businesses – including restaurants, malls, transportation and tourism – when the pandemic started in March 2020. However, under its “new normal” policy[2], the Indonesian government allowed businesses to resume operation, putting people’s lives at stake, relatively early in the pandemic in mid-2020.

Yet the result was still disappointing for the economy. Indonesia’s economy contracted by 2%[3] in 2020, the highest shrinkage since 1998[4].

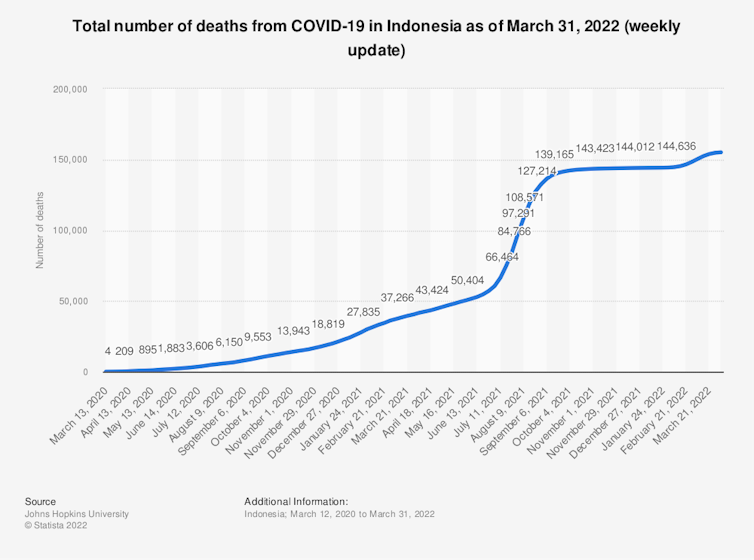

The country also lost 22,000 lives[5] during the year. Due to the Delta variant outbreak, fatalities soared to around 144,000 by the end of 2021[6], putting Indonesia among the countries with the highest mortality rates[7].

Our recent research[8] offers an answer to this health-versus-economy dilemma. We show that a middle-of-the-road policy that saves both business and people’s lives is possible.

By combining two models calculating the impacts of the pandemic on economic activities and on public health, we found a scenario in which the Indonesian government can still grow the economy without risking too many lives.

Under the scenario, the government could have reduced the number of deaths close to 2,000, but at the cost of only around 5% of gross domestic product (GDP, a measure of economic performance) in the same span of time.

But how?

Building the right approaches

We combined health[9] and economic[10] models to generate six possible scenarios connecting health and economic policies.

Both models represent the evolution over time and multiple regions of either an infected population or economic output.

The study links two government interventions: border restrictions and public health policy - both are expected to curb transmission but negatively affect the economy.

We first consider simple scenarios in which all borders are open or closed during the entire time horizon or there are three levels of public health policies being implemented: none, light and medium.

“None” means a complete absence of restrictions to contain the transmission of the virus. This policy exhibits the highest infection rate but with no changes to economic demand or production levels.

A “light” health policy would restricts the services, trade and hotel sectors, thus reducing the transmission rate.

Finally, “medium” represents a harsher but more effective health policy. It places restrictions on construction, manufacturing, transport and communication, and increases the severity of restrictions on services, trade and hotels.