Speaker Johnson’s choice to lead by following the president goes against 200 years of House speakers building up the office’s power

- Written by SoRelle Wyckoff Gaynor, Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Politics, University of Virginia

When the framers of what became the U.S. Constitution[1] set out to draft the rules of our government on a hot, humid day in the summer of 1787, debates over details raged on.

But one thing the men agreed on was the power of a new, representative legislative branch. Article I – the first one, after all – details the awesome responsibilities of the House of Representatives and the Senate[2]: power to levy taxes, fund the government, declare war, impeach justices and presidents, and approve treaties, among many, many others.

In comparison, Article II[3], detailing the responsibilities of the president, and Article III[4], detailing the Supreme Court, are rather brief – further deferring to the preferred branch, Congress, for actual policymaking.

At the helm of this new legislative centerpiece, there was only one leadership requirement: The House of Representatives must select[5] a speaker of the House.

The position, modeled after parliamentary leaders in the British House of Commons, was meant to act[6] as a nonpartisan moderator and referee. The framers famously disliked political parties[7], and they knew the importance of building coalitions to solve the young nation’s vast policy problems.

But this idealistic vision for leadership quickly dissolved.

The current speaker of the House, Mike Johnson[8], a Republican from Louisiana, holds a position that has strayed dramatically from this nonpartisan vision. Today, the leadership role is far more than legislative manager – it is a powerful, party-centric position that controls nearly every aspect of House activity.

And while most speakers have used their tenure to strengthen the position and the power of Congress as a whole, Johnson’s choice to lead by following President Donald Trump[9] drifts the position even further from the framers’ vision of congressional primacy.

Centralizing power

By the early 1800s, Speaker of the House Henry Clay, first elected speaker in 1810 as a member of the Whig Party, used the position to pursue personal policy goals[11], most notably entry into the War of 1812 against Great Britain.

Speaker Thomas Reed continued this trend by enacting powerful procedures[12] in 1890 that allowed his Republican majority party to steamroll opposition in the legislative process.

In 1899, Speaker David Henderson created a Republican “cabinet”[13] of new chamber positions that directly answered to – and owed their newly elevated positions to – him.

In the 20th century, in an attempt to further control the legislation Congress considered, reformers solidified the speaker’s power over procedure and party. Speaker Joseph Cannon[14], a Republican who ascended to the position in 1903, commandeered the powerful Rules Committee[15], which allowed speakers to control not only which legislation received a vote but even the amending and voting process.

At the other end of the 20th century was an effort to retool the position into a fully partisan role. After being elected speaker in 1995, Republican Newt Gingrich expanded the responsibilities of the office beyond handling legislation by centralizing resources in the office of the speaker[16]. Gingrich grew the size of leadership staff – and prevented policy caucuses from hiring their own. He controlled the flow of information from committee chairs to rank-and-file members, and even directed[17] access to congressional activity by C-SPAN, the public service broadcaster that provides coverage of Congress.

As a result, the modern speaker of the House now plays a powerful role in the development and passage of legislation – a dynamic that scholars refer to as the “centralization” of Congress[18].

Part of this is out of necessity: The House in particular, with 435 members[19], requires someone to, well, lead. And as America has grown in population, economic power and the size of government, the policy problems Congress tackles have become more complex, making this job all the more important.

But the position that began as coalition-building has evolved into controlling the floor schedule and flow of information[20] and coordinating and commandeering committee work. My work on Congress[21] has also documented how leaders invoke their power to dictate constituent communication[22] for members of their party and use campaign finance donations[23] to bolster party loyalty.

This centralization has cemented the responsibilities of the speaker within the chamber. More importantly, it has elevated the speaker to a national party figure.

Major legislation passed

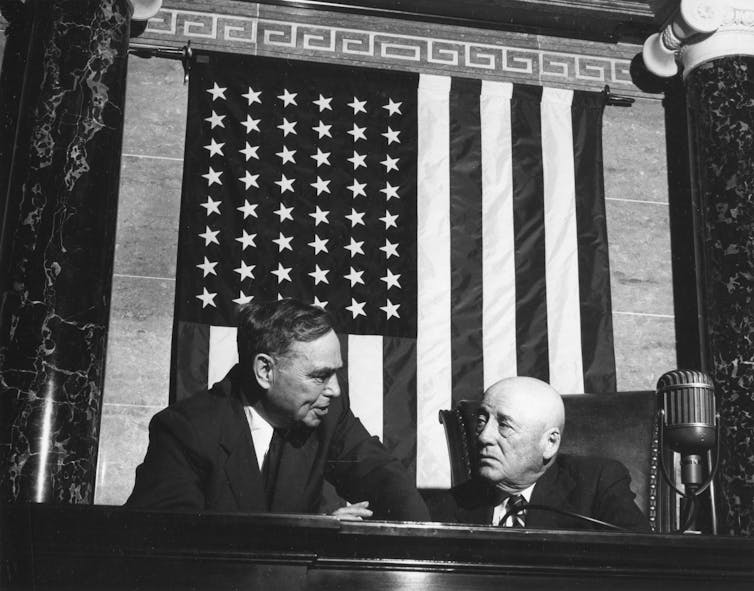

Some successful leaders have been able to translate these advantages to pass major party priorities: Speaker Sam Rayburn, a Democrat from Texas, began his tenure in 1940 and was the longest-serving speaker of the House[24], ultimately working with eight different presidents.

Under Rayburn’s leadership, Congress passed incredible projects, including the Marshall Plan[25] to fund recovery and reconstruction in postwar Western Europe, and legislation to develop and construct the Interstate Highway System[26].

In the modern era, Speaker Nancy Pelosi, a Democrat and the first and only female speaker[27], began her tenure in 2007 and held together a diverse Democratic coalition to pass the Affordable Care Act into law[28].

But as the role of speaker has become one of proactive party leader, rather than passive chamber manager, not all speakers have been able to keep their party happy.

Protecting Congress’ power

John Boehner, a Republican who became speaker in 2011[30], was known for his procedural expertise and diplomatic skills. But he ultimately resigned after he relied on a bipartisan coalition to end a government shutdown in 2014 and avert financial crises[31], causing his support among his party to plummet.

Speaker Kevin McCarthy was ousted in 2023[32] from the position by his own Republican Party after working with Democratic members to fund the government[33] and maintain Congress’ power of the purse.

Although these decisions angered the party, they symbolized the enduring nature of the position’s intention: the protector of Article I powers. Speakers have used their growing array of policy acumen, procedural advantages and congressional resources to navigate the chamber through immense policy challenges, reinforcing Article I responsibilities – from levying taxes to reforming major programs that affect every American – that other branches simply could not ignore.

In short, a strengthened party leader has often strengthened Congress as a whole.

Although Johnson, the current speaker, inherited one of the most well-resourced speaker offices in U.S. history, he faces a dilemma in his position: solving enormous national policy challenges while managing an unruly party bound by loyalty to a leader outside of the chamber.

Johnson’s recent decision to keep Congress out of session[34] for eight weeks during the entirety of the government shutdown indicates a balance of deference tilted toward party over the responsibilities of a powerful Congress.

This eight-week absence severely weakened the chamber. Not being in session meant no committee meetings, and thus, no oversight; no appropriations bills passed, and thus, more deference to executive-branch funding decisions; and no policy debates or formal declarations of war, and thus, domestic and foreign policy alike being determined by unelected bureaucrats and appointed judges.

Unfortunately for frustrated House members and their constituents, beyond new leadership, there is little recourse.

While the gradual, powerful concentration of authority has made the speaker’s office more responsive to party and national demands alike, it has also left the chamber dependent on the speaker to safeguard the power of the People’s House.

References

- ^ framers of what became the U.S. Constitution (www.archives.gov)

- ^ details the awesome responsibilities of the House of Representatives and the Senate (constitution.congress.gov)

- ^ Article II (constitution.congress.gov)

- ^ Article III (constitution.congress.gov)

- ^ must select (constitution.congress.gov)

- ^ meant to act (history.house.gov)

- ^ The framers famously disliked political parties (www.archives.gov)

- ^ speaker of the House, Mike Johnson (www.congress.gov)

- ^ lead by following President Donald Trump (time.com)

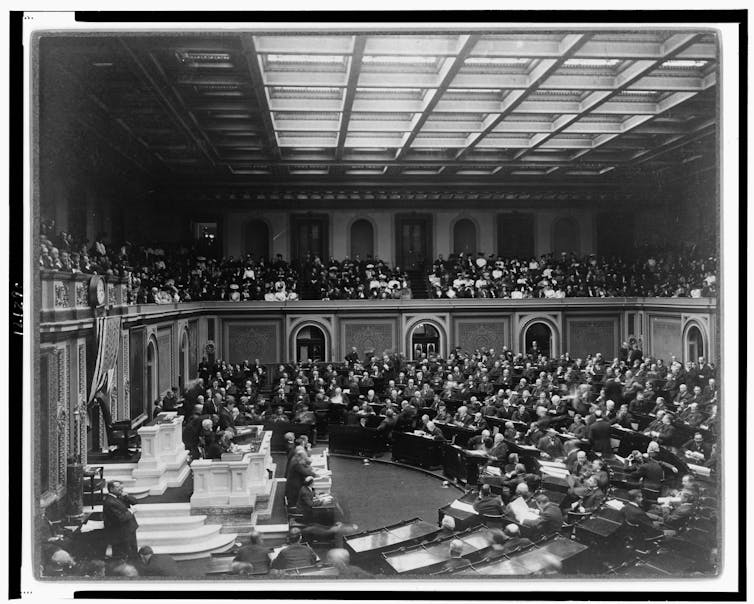

- ^ Artist Frances Benjamin Johnston, Photo by Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ pursue personal policy goals (millercenter.org)

- ^ enacting powerful procedures (history.house.gov)

- ^ created a Republican “cabinet” (history.house.gov)

- ^ Speaker Joseph Cannon (history.house.gov)

- ^ commandeered the powerful Rules Committee (history.house.gov)

- ^ centralizing resources in the office of the speaker (doi.org)

- ^ even directed (www.brandeis.edu)

- ^ “centralization” of Congress (us.sagepub.com)

- ^ The House in particular, with 435 members (www.house.gov)

- ^ flow of information (press.uchicago.edu)

- ^ My work on Congress (batten.virginia.edu)

- ^ constituent communication (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ campaign finance donations (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ longest-serving speaker of the House (history.house.gov)

- ^ Marshall Plan (www.archives.gov)

- ^ Interstate Highway System (www.history.com)

- ^ first and only female speaker (pelosi.house.gov)

- ^ pass the Affordable Care Act into law (doi.org)

- ^ PhotoQuest/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ John Boehner, a Republican who became speaker in 2011 (history.house.gov)

- ^ avert financial crises (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ Speaker Kevin McCarthy was ousted in 2023 (www.pbs.org)

- ^ fund the government (www.pbs.org)

- ^ out of session (www.cbsnews.com)

Authors: SoRelle Wyckoff Gaynor, Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Politics, University of Virginia