Hope and hardship have driven Syrian refugee returns – but many head back to destroyed homes, land disputes

- Written by Sandra Joireman, Weinstein Chair of International Studies, Professor of Political Science, University of Richmond

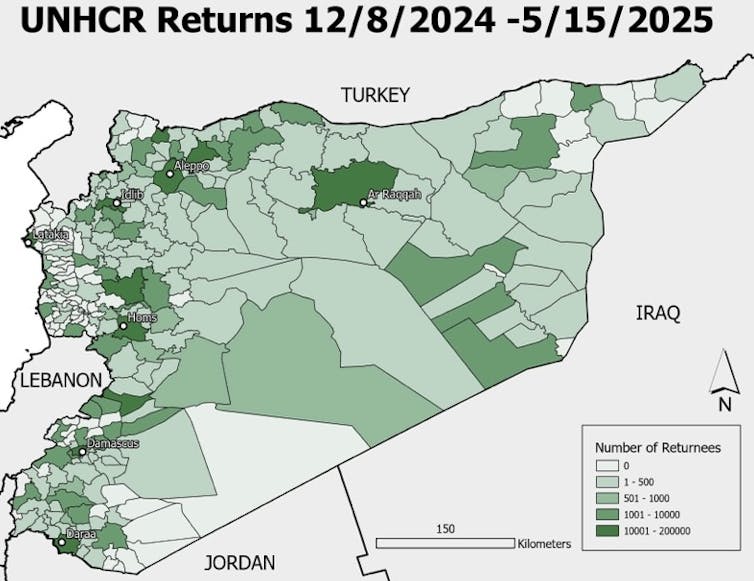

Close to 1.5 million Syrian refugees[1] have voluntarily returned to their home country over the past year.

That extraordinary figure represents nearly one-quarter of all Syrians[2] who fled fighting during the 13-year civil war to live abroad. It is also a strikingly fast pace for a country where insecurity persists[3] across broad regions.

The scale and speed of these returns since the overthrow of Bashar Assad’s brutal regime[4] on Dec. 8, 2024, raise important questions: Why are so many Syrians going back, and will these returns last? Moreover, what conditions are they returning to?

As an expert in property rights and post-conflict return migration[5], I have monitored the massive surge in refugee returns to Syria throughout 2024. While a combination of push-and-pull factors have driven the trend, the widespread destruction of property during the brutal civil war poses an ongoing obstacle to resettlement.

Where are Syria’s refugees?

By the time a rebel coalition led by Sunni Islamist organization Hayat Tahrir al-Sham[6] overthrew the Assad government, Syria’s civil war[7] had been going on for more than a decade. What began in 2011 as part of the Arab Spring protests[8] quickly escalated into one of the most destructive conflicts of the 21st century.

Millions of Syrians were displaced internally, and about 6 million[9] sought refuge abroad. The majority went to neighboring countries, including Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon, but a little over a million sought refuge in Europe[10].

Now, European countries are struggling to determine how they should respond to the changed environment in Syria. Germany and Austria have put a hold on[11] processing asylum applications from Syrians. The international legal principle of non-refoulement[12] prohibits states from returning refugees to unsafe environments where they would face persecution and violence.

But people can choose to return home on their own. And the fall of Assad altered refugees’ perceptions of safety and possibility.

Indeed, the U.N. refugee agency surveys[13] conducted in January 2025 across Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq and Egypt found that 80% of Syrian refugees hoped to return home – up sharply from 57% the previous year. But hope and reality are not always aligned, and the factors motivating return are far more complex than the change in political authority.

Barriers to returns

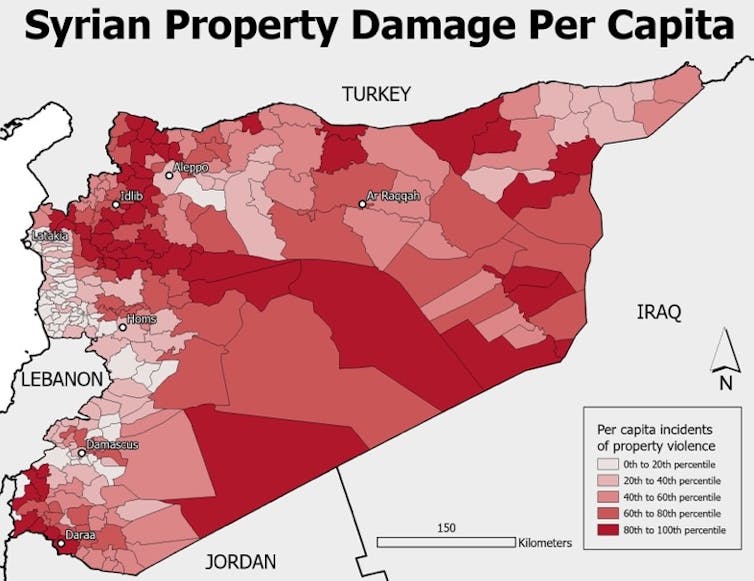

One of the most significant obstacles facing refugees who wish to return is the condition of their homes and the status of their property rights[30].

The civil war caused widespread destruction[31] of housing, businesses and public buildings.

Land administration systems, including registry offices and records, were damaged or destroyed. This matters because refugees’ return requires more than physical safety; people need somewhere to live and proof that the home they return to is legally theirs.

Analysis by the conflict-monitoring group ACLED of more than 140,000 qualitative reports[32] of violent incidents between 2014 and 2025 shows that property-related destruction was more concentrated in inland provinces than in the coastal regions, with cities such as Aleppo, Idlib and Homs[33] sustaining some of the heaviest damage.

References

- ^ 1.5 million Syrian refugees (data.unhcr.org)

- ^ nearly one-quarter of all Syrians (www.unhcr.org)

- ^ insecurity persists (press.un.org)

- ^ overthrow of Bashar Assad’s brutal regime (www.brookings.edu)

- ^ expert in property rights and post-conflict return migration (polisci.richmond.edu)

- ^ led by Sunni Islamist organization Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (www.bbc.com)

- ^ Syria’s civil war (www.cfr.org)

- ^ Arab Spring protests (www.aljazeera.com)

- ^ 6 million (www.unrefugees.org)

- ^ a million sought refuge in Europe (www.euronews.com)

- ^ have put a hold on (www.euronews.com)

- ^ non-refoulement (www.ohchr.org)

- ^ U.N. refugee agency surveys (www.unhcr.org)

- ^ Sandra F. Joireman (data.unhcr.org)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ voluntary return begins (press.umich.edu)

- ^ political control (global.oup.com)

- ^ reconstruction remains incomplete (doi.org)

- ^ sectarian conflicts persist (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ increasing deportations (www.bbc.com)

- ^ structural barriers (doi.org)

- ^ recent violence (www.hrw.org)

- ^ steep drop (mecouncil.org)

- ^ international reductions in humanitarian support (carnegieendowment.org)

- ^ from other post-conflict settings (cup.columbia.edu)

- ^ war in Kosovo (press.umich.edu)

- ^ Recent attacks (www.thenewhumanitarian.org)

- ^ more displacement (www.reuters.com)

- ^ Ercin Erturk/Anadolu via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ condition of their homes and the status of their property rights (www.nrc.no)

- ^ widespread destruction (www.nrc.no)

- ^ 140,000 qualitative reports (acleddata.com)

- ^ Aleppo, Idlib and Homs (documents.worldbank.org)

- ^ Sandra F. Joireman (acleddata.com)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ sometimes violent (www.nytimes.com)

Authors: Sandra Joireman, Weinstein Chair of International Studies, Professor of Political Science, University of Richmond