The law meets its limits – what ‘Nuremberg’ reveals about guilt, evil and the quest for global justice

- Written by B.B. Blaber, Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, Grinnell College

The film “Nuremberg[1]” depicts events surrounding the post-World War II International Military Tribunal – the first and best-known of the Nuremberg trials – which was created to carry out the[2] “just and prompt trial and punishment of the major war criminals of the European Axis.”

Nazi party leaders Hermann Göring, Alfred Rosenberg and Wilhelm Keitel were among the 24 people who ended up being indicted. Six organizations were also indicted, including the Gestapo and the SS. The tribunal, which took place in Nuremberg, Germany, and resulted in 19 convictions, attracted worldwide media attention[3].

Eighty years later, you’ll hear terms like “war crimes” and “genocide” be deployed and debated – whether they’re applied to U.S. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s use of military force in the Caribbean[4] or Israel’s destruction of the Gaza Strip[5].

The public’s understanding of these terms is due, in large part, to the success of the Nuremberg trials and the remarkable degree of international cooperation they required. But the shakiness of international justice today, along with the ongoing complexity of legal and moral conceptions of guilt, shows the limits of the law when it comes to holding the worst of the worst accountable.

Not the first attempt at international justice

These trials were not the first effort to prosecute war crimes in an international court.

The 1921 Leipzig war crimes trials[6] took place to take legal action against Germans accused of war crimes in World War I. These trials, however, were stymied by practical and procedural issues[7], including difficulty bringing the accused to court[8] and locating evidence. They ultimately led to only six convictions – accompanied by light sentences – and even some of those were later overturned.

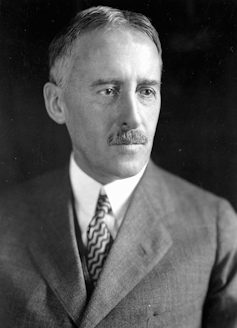

Several years before the end of World War II, officials in the U.K., U.S. and USSR had already begun to discuss what mechanisms would be best for handling a defeated Germany. Some officials, such as U.S. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson[10], argued in favor of trials that adhered closely to American legal principles. Others, like British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, objected, specifically citing the failure of the Leipzig trials[11].

But several aspects were different this time around.

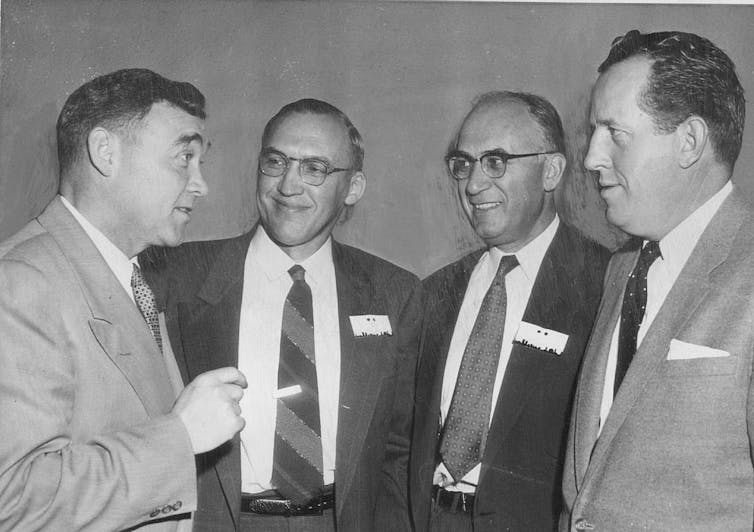

When the four chief prosecutors of the International Military Tribunal, representing the U.K., U.S., USSR and France, filed the indictment for the Nuremberg trials[12], most of the accused were already in custody. The prosecuting attorneys also had access to a trove of Nazi documents[13] to build their cases.

Moreover, beyond a remarkable degree of cooperation[14] among those four nations, there was considerable public interest in and support for the trials. Even swaths of the German public championed them[15].

New categories for crimes

There still needed to be a solid legal basis for the trials. Some defendants argued that their actions, at the time, had been legal under German law.

For these reasons, the charter that established the International Military Tribunal represented a significant development by outlining and defining the specific crimes that would fall under its jurisdiction: war crimes, crimes against peace and crimes against humanity[16].

While the category of war crimes was based on existing international conventions[17], crimes against peace and crimes against humanity had not been previously codified.

The International Military Tribunal proceedings began on Nov. 20, 1945, and the hearings lasted until Sept. 1, 1946. Four judges – one from each of the countries convening the tribunal – presided over the case. Each of the four convening countries also appointed a chief prosecutor to lead the prosecution. Defendants were allowed to select their own legal counsel, subject to the court’s approval[18].

On Oct. 1, 1946, after a month of deliberation, the judges issued the final rulings[19]. Of the 22 individual defendants, 19 were found guilty, 12 of whom were sentenced to death.

Blind spots

One notable detail of the agreement[20] that established the International Military Tribunal was the stipulation that it would be used to punish “the major war criminals of the European Axis[21].”

Atrocities committed by Allied forces, however, were not subject to the court’s scrutiny as possible war crimes, nor were actions taken by Allied governments domestically, including the incarceration of Japanese Americans by the U.S. government[22].

Even U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone[23] expressed misgivings about the legal precedent he saw the trials setting. In a letter[24] discussing International Military Tribunal chief prosecutor Robert H. Jackson – who, at the time, was Stone’s colleague on the Supreme Court – Stone lamented, “I don’t mind what he does to the Nazis, but I hate to see the pretense that he is running a court and proceeding according to common law.”

Questions about the complicity of everyday German citizens and those in Nazi-occupied territories were also left unresolved. To philosopher Hannah Arendt, the verdicts felt rather hollow.

“The Nazi crimes, it seems to me, explode the limits of law,” she wrote[25] to her friend and fellow philosopher Karl Jaspers. “This guilt, in contrast to all criminal guilt, oversteps and shatters any and all legal systems. … We are simply not equipped to deal, on a human, political level, with a guilt that is beyond crime.”

In “Nuremberg,” psychiatrist Douglas Kelley, played by Rami Malek, attempts to understand Hermann Göring’s personality and motivations in order to prevent future atrocities[26]. Kelley assumes Göring will come off as an exemplar of evil. But he finds Göring to be largely ordinary, even likable, and not so different from many Americans[27].

Scholars of the Holocaust and other atrocities continue to grapple with questions around Kelley’s uncomfortable conclusion, and how to make sense of the willingness of seemingly ordinary people[28] to do horrible things[29].

Nuremberg laid the groundwork

While the Nuremberg trials left plenty of further work to do in developing a fair and functional framework for international justice, they represented a landmark development in international law[31], most directly in the adoption of the Nuremberg Principles[32], a set of guidelines regarding what constitutes a war crime.

Furthermore, the Nuremberg Charter specifically disallowed “just following orders” as a defense[33], stating, “The fact that the Defendant acted pursuant to order of his Government or of a superior shall not free him from responsibility.”

Importantly, the International Military Tribunal repeatedly referenced the term “genocide,” which had been coined by Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin[34] less than two years earlier to describe “the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group.” The word appeared in the original indictment[35] and was also used by prosecutors throughout the trial. The Genocide Convention of 1948[36] would go on to codify genocide as an international crime.

The Nuremberg trials also helped to establish precedents used in later international criminal tribunals[37], including those in the wake of the Bosnian war and Rwandan genocide, and influenced the formation of the International Criminal Court[38], which began operating in 2002[39] in The Hague.

A fragile consensus today

After the International Military Tribunal issued its verdicts, Stimson remained a stalwart proponent of the trials he’d championed.

“It was not a trick of the law which brought them to the bar,” he wrote in 1947[41]. It was the “massed angered forces of common humanity.”

In the 80 years since, the world has witnessed countless conflicts and atrocities unfold across the globe, yet only a relatively small number of the alleged perpetrators have been tried before international courts.

Beyond staunch disagreement over how to stop them, you’ll see debates over whether they even constitute crimes in the first place. The legitimacy of international courts is also disputed: In August 2025, the U.S. – which does not belong to the International Criminal Court – imposed sanctions on ICC officials[42] after the court issued arrest warrants against top Israeli officials over alleged crimes in Gaza.

Watching “Nuremberg” in light of Stimson’s claim, you might wonder how to view this current moment vis-à-vis this earlier era.

Have political and social conditions shifted to such an extent that appealing to the “forces of common humanity” is no longer a viable political strategy? Or is the takeaway that there is always value in endeavoring to cultivate some form of consensus – no matter how small – over whether certain lines can never be crossed?

Even if consensus remains elusive, one thing is clear: The world’s knowledge of terms like “genocide” and “crimes against humanity” provides a universally understood way to push back against unfolding atrocities.

References

- ^ Nuremberg (www.imdb.com)

- ^ which was created to carry out the (www.un.org)

- ^ attracted worldwide media attention (books.google.com.mx)

- ^ use of military force in the Caribbean (www.politico.com)

- ^ Israel’s destruction of the Gaza Strip (www.ohchr.org)

- ^ 1921 Leipzig war crimes trials (www.google.com)

- ^ practical and procedural issues (www.historians.org)

- ^ difficulty bringing the accused to court (history.state.gov)

- ^ Library of Congress (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ such as U.S. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson (doi.org)

- ^ specifically citing the failure of the Leipzig trials (press.princeton.edu)

- ^ filed the indictment for the Nuremberg trials (avalon.law.yale.edu)

- ^ a trove of Nazi documents (nuremberg.law.harvard.edu)

- ^ remarkable degree of cooperation (www.roberthjackson.org)

- ^ Even swaths of the German public championed them (libsysdigi.library.uiuc.edu)

- ^ war crimes, crimes against peace and crimes against humanity (www.un.org)

- ^ existing international conventions (avalon.law.yale.edu)

- ^ subject to the court’s approval (scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu)

- ^ the judges issued the final rulings (avalon.law.yale.edu)

- ^ the agreement (avalon.law.yale.edu)

- ^ the major war criminals of the European Axis (www.un.org)

- ^ incarceration of Japanese Americans by the U.S. government (densho.org)

- ^ Harlan Fiske Stone (www.supremecourt.gov)

- ^ In a letter (archive.org)

- ^ she wrote (archive.org)

- ^ in order to prevent future atrocities (books.google.com)

- ^ not so different from many Americans (www.google.com)

- ^ the willingness of seemingly ordinary people (www.google.com)

- ^ to do horrible things (www.google.com)

- ^ The Denver Post/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ landmark development in international law (www.google.com)

- ^ Nuremberg Principles (legal.un.org)

- ^ specifically disallowed “just following orders” as a defense (www.un.org)

- ^ which had been coined by Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin (www.google.com)

- ^ appeared in the original indictment (avalon.law.yale.edu)

- ^ Genocide Convention of 1948 (www.un.org)

- ^ later international criminal tribunals (www.google.com)

- ^ International Criminal Court (www.icc-cpi.int)

- ^ which began operating in 2002 (www.icc-cpi.int)

- ^ Pool Photo/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ he wrote in 1947 (www.foreignaffairs.com)

- ^ imposed sanctions on ICC officials (www.icc-cpi.int)

Authors: B.B. Blaber, Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, Grinnell College