Climate engineering would alter the oceans, reshaping marine life – our new study examines each method’s risks

- Written by Kelsey Roberts, Post-Doctoral Scholar in Marine Ecology, Cornell University; UMass Dartmouth

Climate change is already fueling dangerous heat waves[1], raising sea levels[2] and transforming the oceans[3]. Even if countries meet their pledges to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions that are driving climate change, global warming will exceed what many ecosystems can safely handle[4].

That reality has motivated scientists, governments and a growing number of startups to explore ways to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere[5] or at least temporarily counter its effects[6].

But these climate interventions come with risks – especially for the ocean, the world’s largest carbon sink[7], where carbon is absorbed and stored, and the foundation of global food security[8].

Our team of researchers has spent decades studying the oceans and climate. In a new study, we analyzed how different types of climate interventions[9] could affect marine ecosystems, for good or bad, and where more research is needed to understand the risks before anyone tries them on a large scale. We found that some strategies carry fewer risks than others, though none is free of consequences.

What climate interventions look like

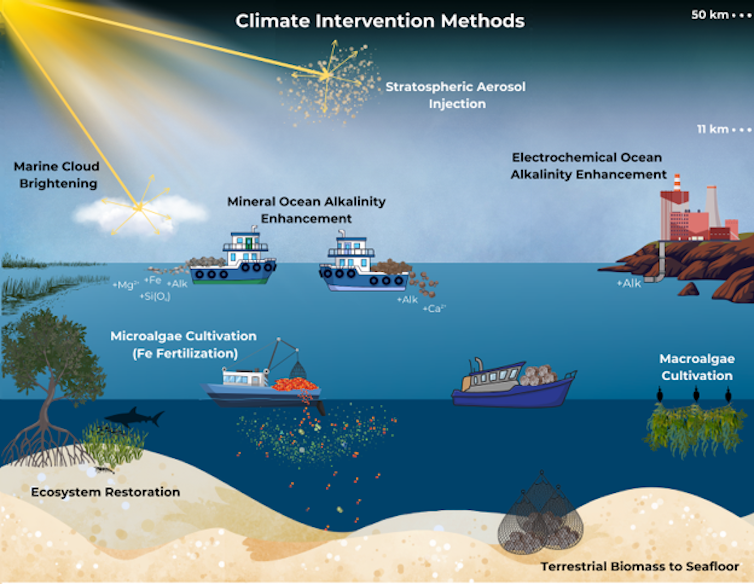

Climate interventions fall into two broad categories that work very differently.

One is carbon dioxide removal[10], or CDR. It tackles the root cause of climate change by taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

The ocean already absorbs nearly one-third[11] of human-caused carbon emissions annually and has an enormous capacity to hold more[12] carbon. Marine carbon dioxide removal techniques aim to increase that natural uptake by altering the ocean’s biology or chemistry.

Biological carbon removal methods capture carbon through photosynthesis in plants or algae. Some methods, such as iron fertilization[13] and seaweed cultivation[14], boost the growth of marine algae by giving them more nutrients[15]. A fraction of the carbon they capture during growth can be stored in the ocean for hundreds of years, but much of it leaks back to the atmosphere once biomass decomposes.

Other methods involve growing plants on land and sinking them in deep, low-oxygen waters where decomposition is slower, delaying the release of the carbon they contain. This is known as anoxic storage of terrestrial biomass[16].

Another type of carbon dioxide removal doesn’t need biology to capture carbon. Ocean alkalinity enhancement[17] chemically converts carbon dioxide in seawater into other forms of carbon, allowing the ocean to absorb more from the atmosphere. This works by adding large amounts of alkaline material, such as pulverized carbonate or silicate rocks like limestone or basalt, or electrochemically manufactured compounds[18] like sodium hydroxide[19].

How ocean alkalinity enhancement methods works. CSIRO.Solar radiation modification[20] is another category entirely. It works like a sunshade – it doesn’t remove carbon dioxide, but it can reduce dangerous effects such as heat waves and coral bleaching by injecting tiny particles into the atmosphere that brighten clouds[21] or directly reflect sunlight back to space[22], replicating the cooling seen after major volcanic eruptions[23]. The appeal of solar radiation modification is speed: It could cool the planet within years, but it would only temporarily mask the effects of still-rising carbon dioxide concentrations.

These methods can also affect ocean life

We reviewed eight intervention types and assessed how each could affect marine ecosystems. We found that all of them had distinct potential benefits and risks[24].

One risk of pulling more carbon dioxide into the ocean is ocean acidification[25]. When carbon dioxide dissolves in seawater, it forms acid. This process is already weakening the shells of oysters[26] and harming corals[27] and plankton[28] that are crucial to the ocean food chain.

Adding alkaline materials, such as pulverized carbonate or silicate rocks, could counteract the acidity[30] of the additional carbon dioxide by converting it into less harmful forms of carbon.

Biological methods, by contrast, capture carbon in living biomass, such as plants and algae, but release it again as carbon dioxide when the biomass breaks down – meaning their effect on acidification depends on where the biomass grows and where it later decomposes.

Another concern with biological methods involves nutrients[31]. All plants and algae need nutrients to grow, but the ocean is highly interconnected. Fertilizing the surface in one area may boost plant and algae productivity, but at the same time suffocate the waters beneath it[32] or disrupt fisheries thousands of miles away[33] by depleting nutrients that ocean currents would otherwise transport to productive fishing areas.

Ocean alkalinity enhancement[36] doesn’t require adding nutrients, but some mineral forms of alkalinity, like basalts, introduce nutrients such as iron and silicate that can impact growth.

Solar radiation modification adds no nutrients but could shift circulation patterns[37] that move nutrients around.

Shifts in acidification and nutrients will benefit some phytoplankton and disadvantage others[38]. The resulting changes in the mix of phytoplankton matter: If different predators prefer different phytoplankton, the follow-on effects could travel all the way up the food chain[39], eventually impacting the fisheries millions of people rely on.

The least risky options for the ocean

Of all the methods we reviewed, we found that electrochemical ocean alkalinity enhancement[40] had the lowest direct risk to the ocean, but it isn’t risk-free. Electrochemical methods use an electric current to separate salt water into an alkaline stream and an acidic stream. This generates a chemically simple form of alkalinity with limited effects on biology, but it also requires neutralizing or disposing of the acid safely[41].

Other relatively low-risk options include adding carbonate minerals[42] to seawater, which would increase alkalinity with relatively few contaminants, and sinking land plants in deep, low-oxygen environments[43] for long-term carbon storage.

Still, these approaches carry uncertainties and need further study.

Scientists typically use computer models[44] to explore methods like these before testing them on a wide scale in the ocean, but the models are only as reliable as the data that grounds them. And many biological processes are still not well enough understood to be included in models.

For example, models don’t capture the effects of some trace metal contaminants[45] in certain alkaline materials or how ecosystems may reorganize around new seaweed farm habitats. To accurately include effects like these in models, scientists first must study them in laboratories and sometimes small-scale field experiments.

Scientists examine how phytoplankton take up iron as they grow off Heard Island in the Southern Ocean. It’s normally a low-iron area, but volcanic eruptions may be providing an iron source. CSIRO.A cautious, evidence-based path forward

Some scientists have argued that the risks of climate intervention are too great to even consider[46] and all related research should stop because it is a dangerous distraction from the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

We disagree.

Commercialization is already underway. Marine carbon dioxide removal startups backed by investors are already selling carbon credits to companies such as Stripe and British Airways[47]. Meanwhile, global emissions continue to rise, and many countries, including the U.S., are backing away from[48] their emissions reduction pledges[49].

As the harms caused by climate change worsen, pressure may build for governments to deploy climate interventions quickly and without a clear understanding of risks. Scientists have an opportunity to study these ideas carefully now, before the planet reaches climate instabilities[50] that could push society to embrace untested interventions. That window won’t stay open forever.

Given the stakes, we believe the world needs transparent research that can rule out harmful options, verify promising ones and stop if the impacts prove unacceptable. It is possible that no climate intervention will ever be safe enough to implement on a large scale. But we believe that decision should be guided by evidence – not market pressure, fear or ideology.

References

- ^ dangerous heat waves (www.ametsoc.org)

- ^ raising sea levels (web.archive.org)

- ^ transforming the oceans (science.nasa.gov)

- ^ exceed what many ecosystems can safely handle (doi.org)

- ^ remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere (www.nationalacademies.org)

- ^ counter its effects (www.nationalacademies.org)

- ^ largest carbon sink (www.annualreviews.org)

- ^ foundation of global food security (worldfishcenter.org)

- ^ analyzed how different types of climate interventions (doi.org)

- ^ carbon dioxide removal (www.ipcc.ch)

- ^ nearly one-third (www.csiro.au)

- ^ has an enormous capacity to hold more (www.annualreviews.org)

- ^ iron fertilization (www.nationalacademies.org)

- ^ seaweed cultivation (www.nationalacademies.org)

- ^ giving them more nutrients (www.nationalacademies.org)

- ^ anoxic storage of terrestrial biomass (doi.org)

- ^ Ocean alkalinity enhancement (www.nationalacademies.org)

- ^ electrochemically manufactured compounds (www.nationalacademies.org)

- ^ sodium hydroxide (doi.org)

- ^ Solar radiation modification (web.archive.org)

- ^ brighten clouds (atmos.uw.edu)

- ^ reflect sunlight back to space (www.nationalacademies.org)

- ^ major volcanic eruptions (science.nasa.gov)

- ^ potential benefits and risks (doi.org)

- ^ ocean acidification (oceanservice.noaa.gov)

- ^ weakening the shells of oysters (www.youtube.com)

- ^ harming corals (doi.org)

- ^ plankton (aoan.aoos.org)

- ^ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory (www.nps.gov)

- ^ counteract the acidity (doi.org)

- ^ nutrients (www.nature.com)

- ^ suffocate the waters beneath it (dx.doi.org)

- ^ disrupt fisheries thousands of miles away (doi.org)

- ^ joydeep/Wikimedia Commons (commons.wikimedia.org)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Ocean alkalinity enhancement (www.nationalacademies.org)

- ^ could shift circulation patterns (doi.org)

- ^ benefit some phytoplankton and disadvantage others (doi.org)

- ^ travel all the way up the food chain (theconversation.com)

- ^ electrochemical ocean alkalinity enhancement (www.nationalacademies.org)

- ^ but it also requires neutralizing or disposing of the acid safely (doi.org)

- ^ adding carbonate minerals (www.nationalacademies.org)

- ^ sinking land plants in deep, low-oxygen environments (doi.org)

- ^ use computer models (doi.org)

- ^ trace metal contaminants (doi.org)

- ^ too great to even consider (doi.org)

- ^ selling carbon credits to companies such as Stripe and British Airways (www.opis.com)

- ^ backing away from (www.bbc.com)

- ^ emissions reduction pledges (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ climate instabilities (doi.org)

Authors: Kelsey Roberts, Post-Doctoral Scholar in Marine Ecology, Cornell University; UMass Dartmouth