Science is best communicated through identity and culture – how researchers are ensuring STEM serves their communities

- Written by Evelyn Valdez-Ward, Postdoctoral Fellow in Science Communication, University of Rhode Island

Lived experiences shape[1] how science is conducted. This matters because who gets to speak for science steers which problems are prioritized, how evidence is translated into practice and who ultimately benefits from scientific advances. For researchers whose communities have not historically been represented in science[2] – including many people of color, LGBTQ+ and first-generation scientists – identity is intertwined with how they engage in and share their work.

As researchers[3] who ourselves[4] belong to[5] communities that have been underrepresented in science, we work with scientists from marginalized backgrounds to study how they navigate STEM – science, technology, engineering and math – spaces. What happens when sharing science with the public is treated as relationship-building rather than a one-way transfer of information? We want to understand the role that identity plays in building community in science.

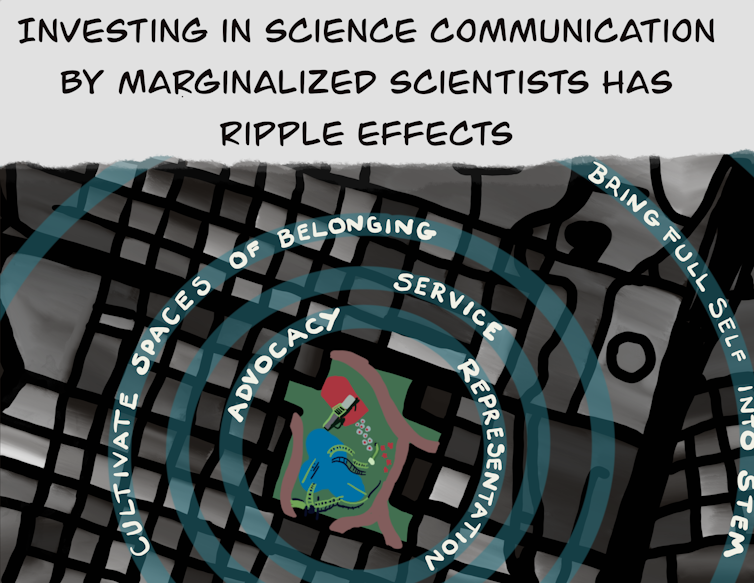

We found that broadening the ways scientists work with the public[6] can bolster trust in science, expand who feels they belong in STEM spaces and ensure that science is working in service of community needs.

STEM spaces as an obstacle course

Science communication[7] involves bridging knowledge gaps between scientists and the broader community. Traditionally, researchers do it through public lectures, media interviews, press releases, social media posts or outreach events designed to explain science in simpler terms. The goals of these activities are often to correct misconceptions, increase scientific literacy and encourage the general public to trust scientific institutions.

However, science communication can look different[8] for researchers from marginalized backgrounds. For these scientists, the ways they engage with the public often focus on identity and belonging. The researchers we interviewed spoke about hosting bilingual workshops with local families, creating comics about climate change with Indigenous youth and starting podcasts where scientists of color share their pathways into STEM.

Instead of disseminating science information through traditional methods that leave little room for dialogue, these researchers seek to bring science back to their communities. This is in part because scientists from historically marginalized backgrounds often face hostile environments in STEM[9], including discrimination, stereotypes about their competence, isolation and a lack of representation in their fields. Many of the researchers we talked to described feeling pressure to hide aspects of their identities, being seen as the token minority[10], or having to constantly prove they belong. These experiences reflect well-documented structural barriers in STEM[11] that shape who feels welcome and supported in scientific environments.

Nic Bennett, CC BY-NC-ND[27]

Making STEM more inclusive

While the participants of our workshop had a variety of goals when it came to science communication, a common thread was their desire to build a sense of belonging in STEM[28].

We found that marginalized scientists often draw on their lived experiences and community connections[29] when teaching and speaking about their research. Other researchers have also found that these more inclusive approaches to science communication[30] can help build trust, create emotional resonance, improve accessibility and foster a stronger sense of belonging[31] among community members.

Nic Bennett, CC BY-NC-ND[27]

Making STEM more inclusive

While the participants of our workshop had a variety of goals when it came to science communication, a common thread was their desire to build a sense of belonging in STEM[28].

We found that marginalized scientists often draw on their lived experiences and community connections[29] when teaching and speaking about their research. Other researchers have also found that these more inclusive approaches to science communication[30] can help build trust, create emotional resonance, improve accessibility and foster a stronger sense of belonging[31] among community members.

Nic Bennett, CC BY-NC-ND[32]

Centering the perspectives and identities of marginalized researchers would make science communication training programs more inclusive and responsive to community needs[33]. For example, some participants described tailoring their science outreach to audiences with limited English proficiency, particularly within immigrant communities. Others emphasized communicating science in culturally relevant ways to ensure information is accessible to people in their home communities. Several also expressed a desire to create welcoming and inclusive spaces where their communities could see themselves represented and supported in STEM.

One scientist who identified as a disabled woman shared that accessibility and inclusivity shape her language and the information she communicates. Rather than talking about her research, she said, her goal has been more about sharing the so-called hidden curriculum for success[34]: the unwritten norms, strategies and knowledge key to secure opportunities, and thrive in STEM.

Identity for science communication

Identity is central to how scientists navigate STEM spaces and how they communicate science to the audiences and communities they serve.

For many scientists from marginalized backgrounds, the goal of science communication is to advocate, serve and create change in their communities. The participants in our study called for a more inclusive vision of science communication[35]: one grounded in identity, storytelling, community and justice. In the hands of marginalized scientists, science communication becomes a tool for resistance, healing and transformation. These shifts foster belonging, challenge dominant norms and reimagine STEM as a space where everyone can thrive.

Helping scientists bring their whole selves into how they choose to communicate can strengthen trust, improve accessibility and foster belonging[36]. We believe redesigning science communication to reflect the full diversity of those doing science can help build a more just and inclusive scientific future.

References^ Lived experiences shape (undsci.berkeley.edu)^ have not historically been represented in science (doi.org)^ As researchers (scholar.google.com)^ who ourselves (scholar.google.com)^ belong to (scholar.google.com)^ broadening the ways scientists work with the public (doi.org)^ Science communication (theconversation.com)^ science communication can look different (doi.org)^ face hostile environments in STEM (doi.org)^ seen as the token minority (doi.org)^ well-documented structural barriers in STEM (doi.org)^ CC BY-NC-ND (creativecommons.org)^ communication focused on conveying information (doi.org)^ much less emphasis on (theconversation.com)^ understanding audiences (theconversation.com)^ facilitating ReclaimingSTEM workshops (doi.org)^ broadly defined science communication (doi.org)^ traditional science communication approaches (theconversation.com)^ audience-centered, identity-focused and emotion-driven (doi.org)^ CC BY-NC-ND (creativecommons.org)^ biological (theconversation.com)^ pattern (theconversation.com)^ formation (theconversation.com)^ infused empathy and feeling (doi.org)^ incorporate their identities (doi.org)^ be of service to their communities (doi.org)^ CC BY-NC-ND (creativecommons.org)^ build a sense of belonging in STEM (doi.org)^ draw on their lived experiences and community connections (doi.org)^ inclusive approaches to science communication (doi.org)^ stronger sense of belonging (doi.org)^ CC BY-NC-ND (creativecommons.org)^ responsive to community needs (doi.org)^ hidden curriculum for success (doi.org)^ more inclusive vision of science communication (doi.org)^ strengthen trust, improve accessibility and foster belonging (journals.sagepub.com)Authors: Evelyn Valdez-Ward, Postdoctoral Fellow in Science Communication, University of Rhode Island

Nic Bennett, CC BY-NC-ND[32]

Centering the perspectives and identities of marginalized researchers would make science communication training programs more inclusive and responsive to community needs[33]. For example, some participants described tailoring their science outreach to audiences with limited English proficiency, particularly within immigrant communities. Others emphasized communicating science in culturally relevant ways to ensure information is accessible to people in their home communities. Several also expressed a desire to create welcoming and inclusive spaces where their communities could see themselves represented and supported in STEM.

One scientist who identified as a disabled woman shared that accessibility and inclusivity shape her language and the information she communicates. Rather than talking about her research, she said, her goal has been more about sharing the so-called hidden curriculum for success[34]: the unwritten norms, strategies and knowledge key to secure opportunities, and thrive in STEM.

Identity for science communication

Identity is central to how scientists navigate STEM spaces and how they communicate science to the audiences and communities they serve.

For many scientists from marginalized backgrounds, the goal of science communication is to advocate, serve and create change in their communities. The participants in our study called for a more inclusive vision of science communication[35]: one grounded in identity, storytelling, community and justice. In the hands of marginalized scientists, science communication becomes a tool for resistance, healing and transformation. These shifts foster belonging, challenge dominant norms and reimagine STEM as a space where everyone can thrive.

Helping scientists bring their whole selves into how they choose to communicate can strengthen trust, improve accessibility and foster belonging[36]. We believe redesigning science communication to reflect the full diversity of those doing science can help build a more just and inclusive scientific future.

References^ Lived experiences shape (undsci.berkeley.edu)^ have not historically been represented in science (doi.org)^ As researchers (scholar.google.com)^ who ourselves (scholar.google.com)^ belong to (scholar.google.com)^ broadening the ways scientists work with the public (doi.org)^ Science communication (theconversation.com)^ science communication can look different (doi.org)^ face hostile environments in STEM (doi.org)^ seen as the token minority (doi.org)^ well-documented structural barriers in STEM (doi.org)^ CC BY-NC-ND (creativecommons.org)^ communication focused on conveying information (doi.org)^ much less emphasis on (theconversation.com)^ understanding audiences (theconversation.com)^ facilitating ReclaimingSTEM workshops (doi.org)^ broadly defined science communication (doi.org)^ traditional science communication approaches (theconversation.com)^ audience-centered, identity-focused and emotion-driven (doi.org)^ CC BY-NC-ND (creativecommons.org)^ biological (theconversation.com)^ pattern (theconversation.com)^ formation (theconversation.com)^ infused empathy and feeling (doi.org)^ incorporate their identities (doi.org)^ be of service to their communities (doi.org)^ CC BY-NC-ND (creativecommons.org)^ build a sense of belonging in STEM (doi.org)^ draw on their lived experiences and community connections (doi.org)^ inclusive approaches to science communication (doi.org)^ stronger sense of belonging (doi.org)^ CC BY-NC-ND (creativecommons.org)^ responsive to community needs (doi.org)^ hidden curriculum for success (doi.org)^ more inclusive vision of science communication (doi.org)^ strengthen trust, improve accessibility and foster belonging (journals.sagepub.com)Authors: Evelyn Valdez-Ward, Postdoctoral Fellow in Science Communication, University of Rhode Island