Why recycling solar panels is harder than you might think − an electrical engineer explains

- Written by Anurag Srivastava, Professor of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering, West Virginia University

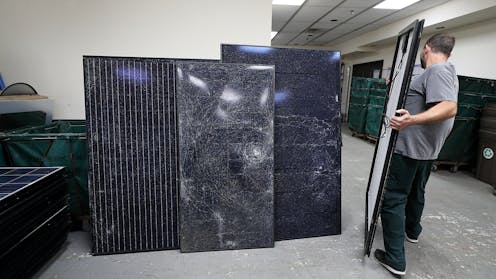

It’s hard work soaking up sunlight to generate clean electricity. After about 25 to 30 years, solar panels wear out[1]. Over the years, heating and cooling cycles stress the materials. Small cracks develop, precipitation corrodes the frame[2] and layers of materials can start to peel apart.

In 2023, about 90% of old or faulty solar panels[3] in the U.S. ended up in landfills. Millions of panels[4] have been installed worldwide over the past few decades – and by about 2030, so many will be ready to retire that they could cover about 3,000 football fields[5].

As an electrical engineer[6] who has studied many aspects of renewable energy, recycling solar panels seems like a smart idea, but it’s complicated. Built to withstand years of wind and weather, solar panels are designed for strength and are not easy to break down.

The cost conundrum

Sending a solar panel to a landfill costs between US$1 and $5[8] in the U.S. But recycling it can cost three to four times as much, around $18[9]. And the valuable materials inside solar panels, such as silver and copper, are in small amounts, so they’re worth about $10 to $12[10] – which makes recycling a money-losing prospect. Improvements in the recycling process may change the economics.

But for now, it’s even hard to reclaim the glass[11] in solar panels. Many layers are glued together and need to be separated before they can be melted down for reuse. And if the separation is not precise enough, the glass that is recovered won’t be of high enough quality to use in making other solar panels or windows. It will be suitable only for lower-quality uses such as fill material in construction projects.

Other panels, usually older ones, may contain small amounts of toxic metals[12] such as lead or cadmium. It can be difficult to tell whether toxic materials are present, though. Even experts have trouble, in part because current tests, such as the toxicity characteristic leaching procedure[13], can give inaccurate results. Therefore, many companies that own large numbers of solar panels just assume their panels are hazardous waste[14], which increases costs for both disposal and recycling. Clearer labels would help people know what a solar panel contains and how to handle it.

If someone wants to recycle a solar panel, and is willing to bear the cost, there aren’t many places in the U.S.[15] that are willing to do it and are equipped to be safe about it.

Designing for a new life

Despite the Trump administration’s cuts to subsidies for solar projects[17], millions of solar panels are already in use in the U.S., and millions more are expected to be installed worldwide[18] in the coming years. As a result, the solar industry is working on ways to minimize waste and repeatedly reuse materials.

Some ideas include sending used solar panels that still work at least a bit to developing nations[19], or even reusing them within the U.S. But there are not clear rules or processes for connecting reused panels to the power grid[20], so reuse tends to happen in less common, off-grid situations rather than becoming widespread.

Future solar panels could also be designed for easier recycling, using different construction methods and materials, and improved processing systems.

Making panels last longer – perhaps as long as 50 years[21] – using more durable materials, weather-resistant components, real-time monitoring of panel performance and predictive maintenance to replace parts before they wear out would reduce waste significantly.

Building solar panels that are more easily disassembled into separate components[22] made of different materials could also speed recycling. Components that fit together like Lego bricks – instead of using glue – or dissolvable sealants and adhesives could be parts of these designs.

Improved recycling methods could also help. Right now, panels are often simply ground up, mixing all of their components’ materials together and requiring a complicated process to separate them[23] out again for reuse. More advanced approaches can extract individual materials with high purity. For example, a process called salt etching[24] can recover over 99% of silver and 98% of silicon, at purity levels that are appropriate for high-end reuse, potentially even in new solar panels, without using toxic acids. That method can also recover significant quantities of copper and lead for use in new products.

A shared journey

Increasing the practice of recycling solar panels has more than just environmental benefits.

Over the long term, recovering and reusing valuable materials may prove more cost-effective than continually buying new raw materials on the open market. That could lower costs for future solar panel installations. If they are fully reused, the value of these recoverable materials could reach over $15 billion globally[26] by 2050.

In addition, recycling panels and components reduces American reliance on materials imported from overseas, making solar power projects less vulnerable to global disruptions.

Recycling also keeps toxic materials out of landfills. That can help ensure a shift to clean energy doesn’t create new or bigger environmental problems. Also, recycling solar panels emits far less carbon dioxide[27] than manufacturing panels from raw materials.

There are already some efforts underway to boost solar panel recycling. The Solar Energy Industries Association trade group is working to collect and share information[28] about companies that recycle solar panels.

Governments can provide tax breaks or other financial incentives for using recycled materials, or ban disposing of solar panels in landfills. California, Washington, New Jersey and North Carolina have enacted laws or are studying ways to manage solar panel waste[29], with some even requiring recycling or reuse[30].

These efforts are important steps toward addressing the growing need for solar panel recycling and promoting a more sustainable solar industry.

References

- ^ solar panels wear out (www.energy.gov)

- ^ precipitation corrodes the frame (doi.org)

- ^ 90% of old or faulty solar panels (www.cnbc.com)

- ^ Millions of panels (www.solarpowereurope.org)

- ^ cover about 3,000 football fields (e360.yale.edu)

- ^ electrical engineer (scholar.google.com)

- ^ David McNew/Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ costs between US$1 and $5 (eridirect.com)

- ^ around $18 (eridirect.com)

- ^ worth about $10 to $12 (climate.mit.edu)

- ^ hard to reclaim the glass (climate.mit.edu)

- ^ contain small amounts of toxic metals (www.epa.gov)

- ^ toxicity characteristic leaching procedure (www.epa.gov)

- ^ assume their panels are hazardous waste (www.epa.gov)

- ^ aren’t many places in the U.S. (www.usitc.gov)

- ^ AP Photo/Gregory Bull (newsroom.ap.org)

- ^ cuts to subsidies for solar projects (theconversation.com)

- ^ millions more are expected to be installed worldwide (www.solarpowereurope.org)

- ^ used solar panels that still work at least a bit to developing nations (www.bloomberg.com)

- ^ connecting reused panels to the power grid (www.pivotenergy.net)

- ^ perhaps as long as 50 years (www.nrel.gov)

- ^ easily disassembled into separate components (ioplus.nl)

- ^ complicated process to separate them (spectrum.ieee.org)

- ^ salt etching (doi.org)

- ^ AP Photo/Gregory Bull (newsroom.ap.org)

- ^ over $15 billion globally (research-hub.nrel.gov)

- ^ emits far less carbon dioxide (doi.org)

- ^ collect and share information (seia.org)

- ^ manage solar panel waste (www.iea.org)

- ^ requiring recycling or reuse (www.eesi.org)

Authors: Anurag Srivastava, Professor of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering, West Virginia University