Would you eat a grasshopper? In Oaxaca, it’s been a tasty tradition for thousands of years

- Written by Jeffrey H. Cohen, Professor of Anthropology, The Ohio State University

Billions of people regularly eat insects[1]. In the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca, chapulines[2] – toasted grasshoppers – stand out as a beloved seasonal treat that follows the start of the rainy season, a period that runs from late May through September.

My new book, “Eating Grasshoppers: Chapulines and the Women who Sell Them[3],” dives into the history and cultural significance of entomophagy (eating insects) and this unique snack.

Chapulineras – the women who sell chapulines – often learn their craft from their mothers and grandmothers. Most will use nets or mesh bags to capture grasshoppers in their “milpa” – alfalfa and maize fields – during the cool, early morning hours.

Teresa Silva, whom I spoke with at her home in Zimatlán, Oaxaca, shared some of her experience:

“I began with my husband’s family, following their traditions after we married. My husband would bring me chapulines in large quantities, and with him and my in-laws’ support, I started to cook and sell [them]. It wasn’t easy at first … but I liked the money I made. Now, I have been selling chapulines for 23 years.”

Prepping chapulines isn’t hard. A dip in boiling water turns the grasshoppers a rich, deep red. Then you toss them on the “comal[4]” – a ceramic or metal cooking surface – with a little garlic, lemon, chile and “sal de gusano[5],” a mixture of ground agave worms, salt and other seasonings. In a few minutes, the grasshoppers are ready to eat.

Culture and cuisine in Oaxaca

Chapulines have been a staple food for thousands of years[6]. Like other insects and their by-products – including honey – grasshoppers are easily digestible, high in protein and an excellent source of vitamins and minerals.

They are also plentiful. Archaeologist Jeffrey Parsons[7] estimates that harvests before the arrival of European settlers might have included 3,900 metric tons of insects and their eggs[8], if not more, annually.

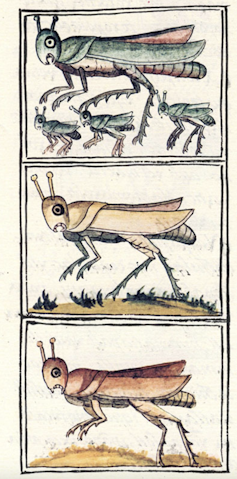

One of the earliest references to chapulines appears in Franciscan Friar Bernardino de Sahagún’s 1577 “General History of the Things of New Spain[9].” Sometimes called the “first anthropologist,” Sahagún describes their importance as a beloved seasonal food in the local diet.

High praise. But perhaps it isn’t surprising that Spanish colonists largely ignored grasshoppers and other Indigenous foods while introducing new crops, animals and unique ways of eating. The Spanish also reorganized life according to the casta system[11] – a racially based hierarchy that restricted the rights and opportunities of Indigenous people.

While chapulines and other insects remained critical to the local diet, the Spanish preferred eating dishes made from the animals and crops they’d brought with them, including wheat and cattle.

Nor were these new foods readily adopted[12] by locals. Indigenous cuisine lacked Spanish parallels. Grains and livestock were not suited to local dishes; furthermore, even as the Spanish colonists had locals grow these new crops, they usually prohibited them from keeping any of the harvest.

An old reliable

Of course, with time, the introduced crops and livestock took hold, and local cuisine incorporated these foods into many of the dishes the world knows today as Mexican.

However, whenever there’s not enough to eat – whether due to discrimination, a natural disaster or a human-made crisis – Mexicans often fall back on edible insects. They were critical following floods and famines in the 18th and 19th centuries. And when Oaxacans fled their homes and farmland during the Mexican Revolution[13], they turned to chapulines as a replacement for more typical proteins like chicken, turkey, beef tripe and pork.

Most recently, when the COVID-19 lockdowns made it nearly impossible to shop for foods, chapulineras created a touchless economy that connected vendors and customers through messaging services like WhatsApp. Some chapulineras also provided no-interest loans[15] to people who could not cover the costs of their orders.

Carmen Mendoza, whom I interviewed at Mercado Benito Juárez in Oaxaca City, described her experience of the lockdown:

“When the pandemic hit, I said to myself, ‘Look, you need to keep selling, but from home.’ I know where I am, and I know my clients. I also know how much people want, how many kilos of chapulines they will buy. So people came to my house. Sometimes they would bring me their harvest, other times they would call and ask for two or three kilos. I could do that.”

The meaning, use and value of chapulines are changing, as Oaxaca has become a popular tourist destination and has been commemorated as a UNESCO heritage site[16]. For foodies and tourists, tasting chapulines is a way to consume and experience the past.

Chapulineras will happily sell to foodies who want to “eat bugs.” But they also know tourists cannot support their market. Visitors usually swoop in for a few days, buy a small handful of chapulines and leave. Most will never return.

And so chapulineras continue to depend on locals whose families have been eating the insects for generations. Many chapulineras have achieved financial security through their efforts, earning incomes that exceed that of most rural women in Oaxaca[17].

In Oaxaca, just as it was 3,000 years ago, chapulines are “what’s for dinner.”

References

- ^ regularly eat insects (smv.org)

- ^ chapulines (www.nationalgeographic.com)

- ^ Eating Grasshoppers: Chapulines and the Women who Sell Them (utpress.utexas.edu)

- ^ comal (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ sal de gusano (www.foodrepublic.com)

- ^ for thousands of years (doi.org)

- ^ Jeffrey Parsons (lsa.umich.edu)

- ^ 3,900 metric tons of insects and their eggs (doi.org)

- ^ General History of the Things of New Spain (www.loc.gov)

- ^ Mexicolore (www.mexicolore.co.uk)

- ^ casta system (www.indigenousmexico.org)

- ^ new foods readily adopted (foodispower.org)

- ^ the Mexican Revolution (www.historytoday.com)

- ^ Artur Widak/NurPhoto via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ also provided no-interest loans (utpress.utexas.edu)

- ^ UNESCO heritage site (whc.unesco.org)

- ^ that exceed that of most rural women in Oaxaca (doi.org)

Authors: Jeffrey H. Cohen, Professor of Anthropology, The Ohio State University