What America’s divided and tumultuous politics of the late-19th century can teach us

- Written by Robert A. Strong, Senior Fellow, Miller Center, University of Virginia

People trying to understand politics in the United States today often turn to history for precedents and perspective. Are our current divisions[1] like the ones that preceded the American Revolution or the Civil War? Did the dramatic events of the 1960s generate the same kind of social and political forces seen today? Are there lessons from the past that show us how eras of intense political turmoil eventually subside?

As a scholar of American politics and the presidency[2], I believe one American historical period is especially worth revisiting in this turbulent moment in the U.S.: the 20 tumultuous years between the presidencies of Ulysses S. Grant and William McKinley in the second half of the 19th century.

The two decades between 1876 and 1896 are usually remembered as a time when the cities in the East grew rich and the West was wild – a “Gilded Age” in New York City[3] and gunslingers on the frontier.

It was also a time when Americans struggled with immigration issues, racial injustice, tariff levels, technological change, economic volatility and political violence.

There was even a president, Grover Cleveland, who served two nonconsecutive terms in the White House[4] – the only time that happened before Donald Trump.

In the elections between Grant and McKinley, the nation was closely divided[5]. No president in those years – not Rutherford Hayes, James Garfield, Chester Arthur, Cleveland or Benjamin Harrison[6] – served for two consecutive terms. No presidential candidate won more than 50% of the popular vote, except the Democrat Samuel Tilden[7]. And Tilden, after winning 50.1% of the ballots cast in 1876, lost in the Electoral College. That happened again in 1888 when Cleveland, the first time he was seeking a second term, won the popular vote but failed in the Electoral College[8].

The narrow victories that characterized presidential politics in the 1870s and 1880s were matched by constant shifts on Capitol Hill. In the 20 years between Grant and McKinley, there were only six years of unified government[9], when one political party controlled the White House, the Senate and the House of Representatives. In the remaining 14 years, presidents encountered opposition in Congress.

The U.S. has the same kind of divided politics today.

Heating up partisanship and raising stakes

President Bill Clinton had two years of unified government; President George W. Bush had less than that[10]. Barack Obama, Donald Trump in his first term and Joe Biden all came into office with party majorities in the House and Senate, and then, like Clinton, their parties lost the House two years later[11].

Divided politics, with close elections and neither party in power for very long, make partisanship more intense[12], campaigns harder fought and the stakes sky high whenever voters go to the polls. That’s part of what produced instability in the second half of the 19th century and part of what produces it today.

Divided government is, of course, one of the most powerful “checks[13]” in the constitutional system of checks and balances. Intense competition between political parties can prevent the national government from making rash decisions and serious mistakes. It can sometimes generate compromise.

But there’s a cost. Political division can also allow critical problems[15] to fester for far too long. The dramatic changes brought on by the Industrial Revolution after the Civil War were not seriously addressed in federal legislation until the Progressive Era[16] early in the 20th century.

In the second half of the 19th century, Congress raised or lowered tariffs[17] – depending on which party controlled the White House and Capitol Hill. The nation debated immigration but only once passed meaningful legislation[18], the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. A long list of issues connected to railroads, banks, currency, civil service, corruption and the implementation of the post-Civil War constitutional amendments were ignored or only partially addressed[19].

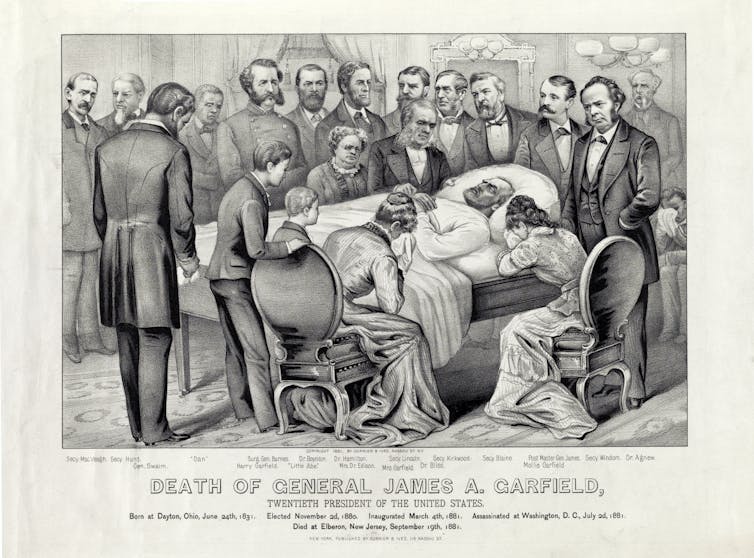

When major legislation was passed in 1883 to create a merit-based civil service[20] – reforming the spoils system of political appointments – it passed because Garfield’s 1881 assassination by a disgruntled federal job seeker[21] temporarily pushed the issue to the top of the national agenda.

Immigration, fake news and riots

Political violence accompanied the period of closely divided national elections[22] in the 1870s and 1880s.

In the 1880 presidential campaign, both candidates – the Republican, Garfield, and the Democrat, Winfield Hancock – called for restrictions on Chinese immigration to the United States[23]. Neither supported the complete ban that many Westerners wanted.

But just before Americans went to the polls, newspapers across the country printed a letter, allegedly written and signed by Garfield, that endorsed an open border[24] to Chinese immigrants. Before anyone could learn that the letter was a fake, there was public uproar. In Denver, an angry mob burned down all the homes in Chinese neighborhoods[25].

There were more incidents of political violence: anti-Chinese riots in Los Angeles in 1871[26], in San Francisco in 1877[27] and in Seattle in 1886[28].

Throughout the 1880s, anti-immigrant nativists targeted immigrants from Italy[29] and sometimes vandalized Catholic churches[30].

Political violence in the South successfully suppressed Black voting rights and reestablished white control[31] of state and local politics.

Realignment

Political division in the second half of the 19th century produced more problems than solutions. How and when did it end, or become less intense?

The simple answer is what political scientists call a “realignment,” a major shift in national electoral patterns.

In 1893, the first year of Cleveland’s second term, the nation suffered a financial crisis followed by a severe economic depression[33]. As a result, McKinley was able to win solid victories in 1896 and 1900[34] and build a Republican coalition that dominated presidential politics until the election in 1932 of Democrat Franklin Roosevelt[35].

It’s not hard to imagine how an economic disaster, or a crisis of some kind, could shake the country out of a period of closely divided politics. But that’s a painful way of building a higher level of national unity.

Can it happen when large numbers of voters get thoroughly frustrated by languishing issues, swings back and forth in Washington, nasty elections and rising political violence?

Perhaps.

But either way – responding to crisis or finding a public change of heart – is a reminder that voters are the ultimate arbiters in a functioning democracy. Today, as in late-19th-century America, elections make a difference. They can mark continued division or they can take the nation in a new, and perhaps more unified, direction.

References

- ^ current divisions (news.syr.edu)

- ^ American politics and the presidency (millercenter.org)

- ^ a “Gilded Age” in New York City (www.nyhistory.org)

- ^ Grover Cleveland, who served two nonconsecutive terms in the White House (www.whitehousehistory.org)

- ^ the nation was closely divided (news.virginia.edu)

- ^ not Rutherford Hayes, James Garfield, Chester Arthur, Cleveland or Benjamin Harrison (www.whitehousehistory.org)

- ^ except the Democrat Samuel Tilden (millercenter.org)

- ^ won the popular vote but failed in the Electoral College (www.britannica.com)

- ^ only six years of unified government (history.house.gov)

- ^ two years of unified government; President George W. Bush had less than that (history.house.gov)

- ^ lost the House two years later (history.house.gov)

- ^ make partisanship more intense (www.universityofcalifornia.edu)

- ^ one of the most powerful “checks (constitution.congress.gov)

- ^ Joshua Lott/The Washington Post via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ Political division can also allow critical problems (theconversation.com)

- ^ Progressive Era (www.loc.gov)

- ^ second half of the 19th century, Congress raised or lowered tariffs (tax.thomsonreuters.com)

- ^ but only once passed meaningful legislation (www.pewresearch.org)

- ^ were ignored or only partially addressed (fscj.pressbooks.pub)

- ^ in 1883 to create a merit-based civil service (www.archives.gov)

- ^ Garfield’s 1881 assassination by a disgruntled federal job seeker (www.nps.gov)

- ^ Political violence accompanied the period of closely divided national elections (theconversation.com)

- ^ called for restrictions on Chinese immigration to the United States (www.britannica.com)

- ^ allegedly written and signed by Garfield, that endorsed an open border (www.hnn.us)

- ^ burned down all the homes in Chinese neighborhoods (www.historycolorado.org)

- ^ anti-Chinese riots in Los Angeles in 1871 (www.lapl.org)

- ^ in San Francisco in 1877 (www.sfgate.com)

- ^ Seattle in 1886 (www.washingtonhistory.org)

- ^ nativists targeted immigrants from Italy (www.loc.gov)

- ^ vandalized Catholic churches (www.politico.com)

- ^ suppressed Black voting rights and reestablished white control (www.pbs.org)

- ^ Glasshouse Vintage/Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ suffered a financial crisis followed by a severe economic depression (academic.oup.com)

- ^ solid victories in 1896 and 1900 (millercenter.org)

- ^ in 1932 of Democrat Franklin Roosevelt (www.britannica.com)

Authors: Robert A. Strong, Senior Fellow, Miller Center, University of Virginia