The celibate, dancing Shakers were once seen as a threat to society – 250 years later, they’re part of the sound of America

- Written by Christian Goodwillie, Director and Curator of Special Collections and Archives, Hamilton College

Director Mona Fastvold’s new film, “The Testament of Ann Lee[1],” features actor Amanda Seyfried in the titular role: the English spiritual seeker who brought the Shaker movement to America. The trailer literally writhes with snakes intercut amid scenes of emotional turmoil, religious ecstasy, orderly and disorderly dancing – and sex. Intense and sometimes menacing music underpins it all: the sounds of the enraptured, singing their way to a fantastic and unimaginable ceremony.

The trailer is riveting and unsettling – just as the celibate Shakers were to the average observer during their American emergence in the 1780s.

I sit on the Board of Trustees of Hancock Shaker Village[2] in Massachusetts, where some of the film was shot, though I have not seen the film, which is due to be released on Christmas Day. I was the curator at Hancock from 2001 to 2009 and have studied the Shakers for more than 25 years, publishing numerous books[3] and articles[4] on the sect.

Fascination with the Shakers is enduring, as are they. The sect once had several thousand members; today, three Shakers remain[5], practicing the faith at their village in Sabbathday Lake, Maine[6], as they have since 1783.

Mona Fastvold’s film depicts the group’s early years in North America.Many characteristics of Shaker life and belief set them apart from other Protestant Christians, but their name derives from one of the most obvious. Early Shakers manifested the holy spirit that they believed dwelled within them by shaking violently in worship. While they called themselves “Believers,” observers dubbed them “Shakers[7].” Members eventually adopted the name, although officially they are the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing.

The Shakers developed unique worship practices in both music and dance that expressed their faith. Until the 1870s, Shaker music was monophonic, with a single melodic line[8] sung in unison and without instrumental accompaniment. Many of their melodies, Shakers said, were given to them by spirits. Some of these charmed and haunting strains[9] have permeated through broader American musical culture.

New form of family

The Shakers first began to organize in Manchester, England, in 1747. By 1770, they came to believe that the spirit of Christ had returned through their leader, “Mother” Ann Lee. However, “Mother Ann was not Christ, nor did she claim to be,” the Shakers state[10]. “She was simply the first of many Believers wholly embued by His spirit, wholly consumed by His love.”

In 1774, Lee led eight followers to North America, settling near what is now Albany, New York[11]. As is still true today, Shakers held their property in common, following the model of the earliest Christians that is recorded in the Bible’s Book of Acts[12]. At its height, the movement had 19 major communities.

Shakers work out their salvation each day by physical and spiritual labor. They do not subscribe to the common Christian doctrine that Jesus’ death atoned for the sins of mankind. And Shakers are celibate[14] – one of the practices that most startled their neighbors in 18th- and 19th-century America. Lee taught that humanity could not follow Christ in the work of spiritual regeneration, or salvation, “while living in the works of natural generation, and wallowing in their lusts.” For Shakers, celibacy is one way people can reunite their spirits with God, who they believe is dually male and female[15].

Almost every Shaker, therefore, joined the faith as a convert, or the child of converts. Families who joined their communities were effectively dissolved: Husbands and wives became brothers and sisters; parents and children the same. Early accounts[16] report that, in extreme instances, children publicly denounced their parents and pummeled their genitals in an effort to subdue the flesh and its earthly ties.

Shaking with the spirit

The Shakers of Lee’s day – now seen as American as apple pie – were regarded as a fundamental threat to society[17]. In part, that stemmed from their perceived dissolution of families. But many outsiders were also alarmed by their ritual dances, whose intensity and emotion demonstrated a physicality seemingly incongruous with their celibacy.

In the early years, Shaker worship was an unbridled individual expression of spiritual enthusiasm. Eventually, it transformed into highly choreographed dances. At first, these were agonizingly slow and laborious series of movements designed to mortify the flesh – to help the spiritual overcome the physical – and instill discipline and union among the members.

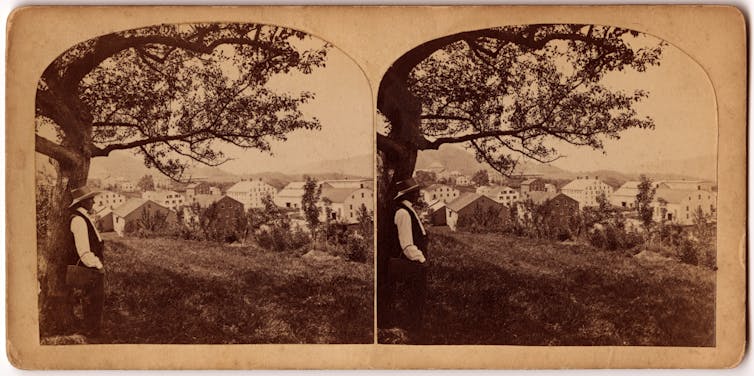

Historians and reenactors have recreated some Shaker dances.What kind of music accompanied such striking movements? The earliest Shaker songs, including ones attributed to Lee, have no intelligible language[18]. Rather, they were sung using vocalized syllables or “vocables,” such as lo-de-lo or la-la-la or vi-vo-vum. Shakers invented a new form of notation to record their songs, using letters adorned with a variety of hashmarks to denote pitch and rhythm.

Early observers of the Shakers noted the effects of their unique musical practice[19]:

They begin by sitting down and shaking their heads in a violent manner, … one will begin to sing some odd tune, without words or rule; after a while another will strike in; … after a while they all fall in and make a strange charm … The mother, so called, minds to strike such notes as makes a concord, and so form the charm.

The Shakers were meticulous recordkeepers regarding every aspect of community life. Music was no exception[20]. More than 1,000 volumes of Shaker music survive in manuscript: tens of thousands of songs dating from Lee’s day to the mid-20th century.

Scholars, musicians and researchers have extracted treasures from this repertoire. Most notably, composer Aaron Copland adapted Elder Joseph Brackett’s famous 1848 tune “Simple Gifts” for “Appalachian Spring”: the ballet that won Copland a Pulitzer in 1945[21]. Hidden gems must still abound in the remaining unplumbed depths of Shaker manuscript songbooks.

In contrast, the Shakers left few detailed instructions for their dance. But eyewitness accounts abound, and scholars have made careful and respectful reconstructions[22].

Living faith

Fastvold’s film evokes the chaotic, violent world of the first Shakers in America, who converted farm families along the New York-Massachusetts border during the Revolutionary War. Some outsiders regarded the sect as an English plot to neutralize the populace with religious fervor[23], opening the way for a British reconquest of New England.

The director’s vision, incarnated by Seyfried’s bewitching presence and voice, invokes the uncanny atmosphere of early Shakerism. However, Shakerism is a living, ever-changing faith, whose presence in America is older than the country itself. The fact is, Shakers have not regularly danced in worship since the 1880s – or less than half of the total time the sect has endured.

Outsiders judged and named the Shakers in reaction to their external qualities in worship. The movement’s endurance and core, however, lies in its spiritual teachings. As the Believers asserted in their 1813 hymn “The Shakers[25],” “Shaking is no foolish play.”

References

- ^ The Testament of Ann Lee (www.imdb.com)

- ^ Hancock Shaker Village (hancockshakervillage.org)

- ^ numerous books (www.hamilton.edu)

- ^ and articles (doi.org)

- ^ three Shakers remain (www.wbur.org)

- ^ their village in Sabbathday Lake, Maine (maineshakers.com)

- ^ observers dubbed them “Shakers (daily.jstor.org)

- ^ a single melodic line (youtu.be)

- ^ charmed and haunting strains (www.umasspress.com)

- ^ the Shakers state (maineshakers.com)

- ^ settling near what is now Albany, New York (www.nps.gov)

- ^ the Bible’s Book of Acts (www.biblegateway.com)

- ^ Digital Collections, Hamilton College Library (litsdigital.hamilton.edu)

- ^ And Shakers are celibate (archive.org)

- ^ dually male and female (maineshakers.com)

- ^ Early accounts (quod.lib.umich.edu)

- ^ a fundamental threat to society (doi.org)

- ^ have no intelligible language (commonplace.online)

- ^ their unique musical practice (quod.lib.umich.edu)

- ^ Music was no exception (commonplace.online)

- ^ won Copland a Pulitzer in 1945 (www.pulitzer.org)

- ^ careful and respectful reconstructions (www.youtube.com)

- ^ neutralize the populace with religious fervor (quod.lib.umich.edu)

- ^ Gregory Rec/Portland Press Herald via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ their 1813 hymn “The Shakers (www.umasspress.com)

Authors: Christian Goodwillie, Director and Curator of Special Collections and Archives, Hamilton College